Individualism, Art and Craft: Reading Bruce Lee by the Numbers

Interpreting Bruce Lee

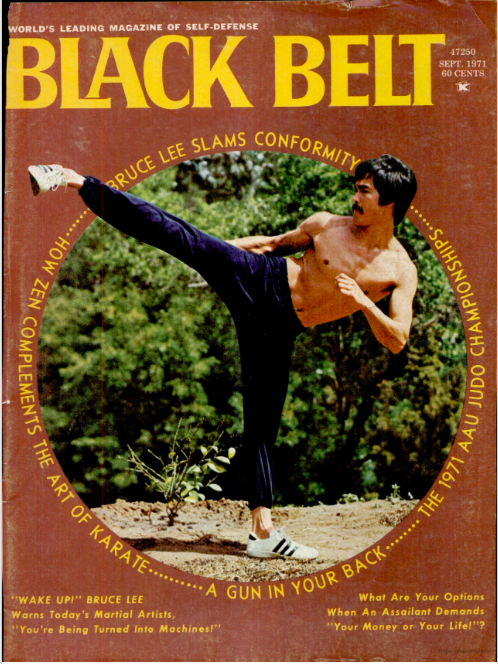

We may debate lists of the 20th century’s most influential martial artists,* but when it comes to written texts, there is simply no question. “Liberate Yourself from Classical Karate,” Bruce Lee’s 1971 manifesto, first appearing in the September issue of Black Belt magazine, has been reprinted, read, criticized and commented upon more than any other English language work. Like many aspects of Lee’s legacy, it has generated a fair degree of controversy. But what interests me the most is the scope and character of its audience.

One might suppose that Lee’s essay would have been read primarily by the Karate students that the title hailed, or perhaps by the generations of Kung Fu students who have come to idolize him. And it is entirely understandable that this text has assumed an important place within the Jeet Kune Do community. Yet its title notwithstanding, Lee never intended this piece as a narrow argument. Nor, when we get right down to it, was Lee actually trying to convince anyone to quite Karate in favor of another style. Such nationalist or partisan concerns were a feature of the earlier phase of his career. By 1971 Lee was concerned with more fundamental issues.

Yet all of these statements are really my own personal readings, and as such they open the door to questions of interpretation. What are the most valid ways to read Lee’s famous essay? And what sorts of interpretations might be unsupportable, what Umberto Eco called “overinterpretations” (See “Interpretation and Overinterpretation: World, History, Texts” (Cambridge University 1990). I have it on good authority that two of my friends are currently preparing a debate on this text, and what it suggests about the validity of various theories of interpretation, which will appear in a future issue of Martial Arts Studies.

With that on the horizon, I am hesitant to venture too far into the same territory. Yet if he were here, Umberto Eco’s would probably point out that a close reading reveals that Lee seems to have had some well-developed thoughts on how his essay should be read, and what sorts of interpretations of this text (and the Jeet Kune Do project more generally), might be considered valid. Lee begins his argument with the well known story of the Zen master overflowing a cup of tea precisely to head off responses to his work that might be classified as “arguments from authority.” Indeed, in the very next paragraph he tells his readers that he has structured his essay like the traditional martial arts classes that they are all so familiar with. First the mental limbering up must happen so that one’s received bodily (or mental) habits can be set aside. Only then is it possible to see events as they actually are, without resorting to the crutch of style (or perhaps theory) to tell you what you are perceiving.

As a social scientist I am very suspicious of those who claim to be able to put “theory” aside and to simply see a situation for what it really is. As one of my old instructors colorfully declared, no such thing is possibly. “Theory is hardwired into our eyeballs.” It is fundamental to how our brains make sense of raw stimulus. We all have so many layers of mental habit, training and predisposition that the notion of setting it aside is fundamentally misguided. Much the same could be said of our bodily predispositions. Lee is correct in that one can set aside style. But the more basic structures that Marcel Mauss called “techniques of the body”, or Bourdieu’s socio-economically defined (and defining) “habitus,” are not things that can ever really be set aside. Seeing the world with no filter at all, dealing with pure objective reality, is not possible, no matter how much enthusiasm Lee generates for the project.

On a personal level I suspect that while we all strive (and we should strive) to empty our cups, the best we can actually do is to try and be aware of the unique perspectives that each of us bring to an event. For instance, when Lee composed the arguments and images that make up this essay, it was with the intention of constructing what Eco called a “model reader”, someone who would become sympathetic to the arguments that he was trying to make. This was not necessarily a reader who would quit his karate class and put on a JKD shirt (though that might happen). Again, Lee was pretty explicit about his aims. He wasn’t trying to make America’s martial artists more like him in a technical sense. Rather, it was enough if they simply began to “leave behind the burdens of pre-conceived opinions and conclusions,” and base their training strategies on personal observations of what actually happened rather than someone else’s notions of what should happen. In essence, Lee was not so much proposing that America’s martial artists change styles (something that by definition could only be a pointless, lateral, move). Rather, he wanted them to begin to think seriously about how exactly they knew what they knew. He wanted them to change epistemologies.

We can say this much with confidence. Yet knowing everything that Lee wanted, or intended, as an author is tricky. This was not a long essay, and while key points can be teased out (e.g., a surprising degree of faith in the individual and a notable suspicion of all sources of social authority), many lines in the essay remain open to interpretation. It is the sort of text that rewards a very close, sentence by sentence, reading. Even then, all we can really know is the intention of this essay, a linguistic artifact created at a specific moment in 1971. It is interesting to speculate as to what a much younger Lee would have made of this text. And by the end of his life in 1973 his thoughts on the value of Jeet Kune Do seem to have evolved rather dramatically. While we might fruitfully debate the interpretation of Lee’s text, the interpretation of its author remains a much more difficult task.

Still, Lee attempted to make it clear that certain interpretations of his text were out of bounds. It is that authorial strategy that actually brings Eco’s approach to mind as possible interpretive strategy. He notes that a proper reading would be a humanist one. For Lee the martial arts are properly a matter of individual human activity rather than the exclusive property of nations or groups. He notes that his essay should not be seen as a polemic by a Chinese martial artist against the Japanese bushido. Nor should he be read as proposing a new style or system of martial training. It also seems clear that Lee himself is the subject of the extended metaphor on page 25. It is the author himself who in the past “discovered some partial truth” and “resisted the temptation to organize” it. The whole story is directed towards Lee’s own students who in their enthusiasm to wrench meaning from one part of Lee’s text (or bodily practice) might fall prey to Eco’s process of “overinterpretation.”

All of this is only my interpretation of Lee’s essay, and it goes without saying that I am a type of reader that this text never anticipated. After all, the academic study of the martial arts did not really exist in 1971, certainly not the way that it does now.

What audience did Lee, as an author, seek? What sort of “model reader” did this text intend to create? And why was there even a need to issue a call for liberation in the first place? One might suppose that the value of freedom, self-expression and increased fighting prowess would simply be self-evident. The fact that Lee is extolling their virtue, and calling for a fundamental change in the sources of authority that martial artists are willing to accept, suggests that it was not.

Paint by Numbers

Eco may be correct that it is essentially impossible to divine the true intent of an author simply from the resulting text. Yet the complexity of that task pales in comparison with the challenge of reconstructing how his or her readers responded to that text at a given point in history. After all, the author had the good sense to leave us with a text (even if his meanings may have been unclear). The readers, more often than not, left nothing but nods of agreement or groans of frustration deposited within the etheric sphere. Trying to reconstruct their experience through our own empathic imagination might really be an exercise in “organized despair,” to borrow a phrase from Lee. Yet it is precisely in those moments, where the expectation of the reader and the intention of a text clash, that brief bursts of light are created. And this fading conflict can suggest some of the critical features that once defined a historical landscape. While difficult, it is worthwhile to try and discover something about the “model readers” who struggled with, and were organized by, this text. Indeed, I actually find the readers of this essay even more interesting (and vastly more sociologically significant) than its author. Yet we know so much less about them.

While few readers took the time to provide contemporaneous documentation of their first reading of this essay (I know of no such record), it would not be correct to say that they left no evidence of their passing. For one thing, the 1970s produced a rich material and symbolic record which suggests some interesting hypotheses about the sorts of audience that Lee would have encountered. Two such artifacts are currently hanging on the wall of my living room.

They appear in the form of pair of paint by number landscapes, illustrating a wintery New England day so picturesque that one is quite certain that it never happened. These paintings were completed by a woman in 1971, the same year that Lee’s essay first appeared. One suspects that if he had taken an interest in art criticism Lee would have had much to say about my paintings. With a few choice substitutions his famous essay could easily be retitled “Liberate Yourself from the Paint by Number Kit” and it would read almost as well.

That, seemingly flippant, observation reveals an important clue about the sorts of readers (and martial artists) that Lee was addressing. We don’t have a large body of informed martial arts criticism dating from the 1970s, but we do have a vast literature on the criticism of the visual arts. And several critics explicitly addressed the paint by numbers fad. The sorts of arguments that they made sound, at least to my ear, uncannily like the points that Lee was trying to make.

By 1971 the paint by number phenomenon was already a well-established part of American middle class landscape (much like the neighborhood judo club). These kits were originally conceived of by an artist named Dan Robbins and Max S. Klein, the owner of the Palmer Paint Company. After the end of WWII Americans leveraged their increased rights in the workplace, and a period of unprecedented economic growth, to create a new golden age of the leisure economy. The forty-hour work week meant that workers had more free time than ever before, and they had enough income to fill those hours with an ever expanding range of activities. The visual arts were increasingly popular, but for most people doing their own paintings remained an aspirational dream. Robbins and Klein decided that simple kits, which required only an ability to color within the lines, would provide Americans with many hours of relaxation while selling an unprecedented amount of paint. Their initial run of kits, which attempted to educate consumers about the latest trends in serious modern art, did not sell particularly well. But when more nostalgic images of the countryside, animals, dancers and the “exotic East” were introduced, it was clear that a cultural phenomenon had been born.

This did not please most of the art critics of the day. The lack of creativity, indeed, the process of near mechanical reproduction, involved in these “paintings” came to symbolize the worst aspects of 1950s social conformity. [Note also that cover of the 1971 Black Belt issues has Lee hyperbolically warning America’s martial artists that they are being transformed into machines]. In the view these critics, individuals were drawn to art because they wanted to experience creativity. Yet these kits promised them basic results only by foreswearing any degree of individual expression. When the critics imaged millions of (near identical) Mona Lisas hanging on the walls of the millions of (near identical) tiny homes which populated America’s postwar landscape, they found themselves drowning in a nightmare of suburban mediocrity.

This was precisely the cultural milieu that inspired Umberto Eco to undertake his cross-continental road-trip, explicitly focusing on the question of simulation in the American imagination of fine art, which would result in his essay “Travels in Hyperreality.” This is a work that has proved important to my own understanding of the role of cultural desire within the martial arts. Still, the judgement of the contemporary critics was clear. Art was the product of individual inspiration and struggle with a constantly changing world. These paintings were not art. At best they were a mechanically reproduced “craft.”

Yet there has always been a strain of American popular culture within which such an assertion does not work as an invective. The entire turn of the century “arts and crafts” movement (seen in architecture, furniture, and the graphic arts) explicitly rejected the elitism of high art and instead asked what sort of social benefit could be derived from the support of, and participation in, wholesome crafts in which people enriched and beautified their environments while supporting local craftsmen. Nor do most of the post-war individuals who spent their afternoons with these kits seem to have aspired to be “artists.” While such questions may have been critical to the critics, these were not categories that structured the lives of these consumers.

Paint by numbers was popular because the process was enjoyable. People found these kits to be relaxing. Further, the idea that one could make an object suitable for display in their own homes was intrinsically rewarding. In light of this, the critic’s emphasis on individual creativity and authenticity seems to have been misplaced. No one bought a Mona Lisa kit because they wanted to express their authentic “inner vision.” Rather, they wanted to enter into a dialogue with that specific piece of art. They sought to understand someone else’s vision, and to be part of a community that appreciated that.

The entire genera of paint by numbers is marked with an almost overwhelming air of nostalgia. This was an exercise in cultivating (and satisfying) a desire for preexisting categories of meaning. Through the reproduction of different types of art (religious images, Italian masters, American landscapes, dancing figures, Paris cityscapes, etc….) individuals sought to align themselves with, and appropriate, some specific aspect of pre-existing social authority. Make no mistake, the creation of real art is hard work. Yet paint by numbers succeeded as a popular medium because it took seriously the notion of leisure. The physical artifacts that it generated were, in many ways, secondary to the social and psychological benefits created.

A traditional class within the Japanese martial arts might seem quite different than a paint by number kit. Ideally the later generates very little sweating and yelling, while the former practically demands it. Yet it is no coincidence that these pursuits both exploded into America popular culture in the 1950s, driven by the growth of the post-war leisure economy. Both sought to simplify complex elite activities and present them to the masses in such a way that they could be easily mastered. Indeed, the standardized kata and training methods seen in Meiji and Showa era martial arts schools seem to have appealed to the same social sensibilities that Robbins and Klein sought to capitalize on.

Nor do questions of individuals or individual expression figure that prominently into the early post-war martial arts discourse. We should hedge this last point as, while they were more visible, the Asian martial arts remained outside of the hegemonic aspects of Western culture (Bowman 2017). To practice Judo in the 1950s was an expression of individual choice and values in a way that would not have been true of Japanese school children taking a Judo class in 1937. And it is certainly true that when many returning GI’s (and later Korean and Vietnam veterans), took up these pursuits. Some sought solace, while others were looking for a source of martial excellence. For instance, Donn F. Draeger’s letters to R. W. Smith make it clear that he was quite interested in the Japanese koryu, but had no interest in contemporary Chinese martial arts, because Japan had performed well on the battle field, and Chinese troops, by in large, had not (Miracle 2016).

Yet I doubt that Draeger was expecting to find real, unfiltered, free-style violence within the traditional dojo. One suspects that most of these vets, at least the ones who had actually seen combat, would have had enough of that on the beaches of the Pacific. What seems to have motivated many of these early students was not so much the search for “realism,” as it was the search for a “cultural essence.” Knowing the reality of warfare, one wonders whether they were freed from petty debates about the “reality of the octagon” (or its post-war equivalents).

Draeger threw himself into highly ritualized styles of Japanese swordsmanship not because he believed this was what a “scientific street fight” actually looked like. He seems to have been looking for a deeper set of answers as to how men had achieved victory in combat in the past. The answers were partially technical, but they also included more. Rightly or wrongly, it was clear to Draeger that (some) Japanese martial artists had the answers, while the Chinese did not. His friend and fellow researcher, R. W. Smith, came to a different set of conclusions after his own experiences with Chinese martial artist while living in Japan and Taiwan. Their martial arts research was not so much about expressing individualism in the abstract (though Draeger’s interests in body building did eventually take him in that direction), but understanding systems of social authority that had allowed individuals to do amazing things.

Conclusion: A Debate Between Readers

These duel excursus into the graphic arts and the early days of hoplology suggests how one group of readers may have approached Lee’s classic essay. In larger cultural terms, Lee’s essay may be less daring than it first appears. While such discussions were novel in the small world of Western martial arts practice, art and culture critics had been making points very similar to Lee’s for decades. They had been doing that because activities that were structurally similar to the practice of the traditional martial arts had become increasingly common within American society since the early 1950s. Lee is often portrayed as a radical or iconoclastic thinker, but when placed next to these critics his calls for individual expression and authenticity within the arts actually replicate the era’s elite social values. More radical, in some senses, were the voices that argued for primacy of craftmanship over art, or for a turn towards a foreign (even colonial) set of cultural values as a way of dealing with the malaise of modern life.

The issues being debated by the martial artists of the 1970s (and still today) are so fundamental that Lee’s essay was bound to generate disagreement. The editors of Black Belt anticipated this. It may be worth reading Lee’s essay in comparison with the issue’s opening editorial on the importance of bowing and traditional etiquette, as well as its final article titled “The Legacy of the Dojo” by David Krieger (50). The first piece contains a quote by an anonymous Chinese martial artist (who may well be Bruce Lee himself as he often haunted the magazine’s offices) praising the efforts of Japanese martial artists to bring morality into their training halls while noting the often-disrespectful ways that Chinese students discussed their own teachers. The two pieces, which both make oblique arguments for the acceptance of traditional modes of social authority within the Asian martial arts, seem to offer an intentional counterpoint to some of Lee’s more individualistic notes.

When we consider the larger social trends in post-war America, and read Lee’s essay in conjunction with the pieces that bookend the September 1971 issue, the parameters of the debate become clearer. Then, as now, the martial arts could be seen either as a vehicle for understanding traditional modes of social authority, or as a means of breaking them down. Readers split on this issue, just as they still do today. It is precisely this ongoing dialectic that allows the ostensibly “traditional” Asian martial arts to fill so many social roles in the modern Western world. This essay’s genius lies not in its ability to convince one side or the other, but in its ability to draw successive generations into the discussion.

*For the record, Kano Jigoro has my vote for the 20th century’s most influential martial artist.

oOo

If you enjoyed this post you might also want to read: Explaining “Openness” and “Closure” in Kung Fu, Lightsaber Combat and Modern Martial Arts

oOo