–

科學化的國術

SCIENTIFIC MARTIAL ARTS

吳志青

by Wu Zhiqing

[originally published as 應用武術中國新體操 Using Martial Arts to Make China’s New Calisthenics in 1919/1920, (known more commonly as just 中國新體操 China’s New Calisthenics), then published in serialized form in 武術 Martial Arts Magazine as 應用科學之國術 Applying Science to Martial Arts, 1921, and finalized in book form during 1921 as 科學化的國術 Scientific Martial Arts]

–

體育良師

Physical education is an excellent teacher indeed.

王正廷題

– calligraphy by Wang Zhengting

–

志氣精神

On willpower, energy, essence, spirit:

三軍不可奪者志也

To be unconquerable even by armies – that is what it means to have willpower.

百折而不撓者氣也

To be sent down many detours and yet never be frustrated – that is what it means to have energy.

專一而不雜者精也

To be focused on one thing and not distracted by many – that is what it means to have essence.

聖而不可知者神也

“To have wisdom beyond the comprehension of others – that is what it means to have spirit.” [Mengzi, chapter 7b]

閩侯林傳甲敬題

– calligraphy by Lin Chuanjin of Minhou County

–

沈序

PREFACE BY SHEN ENFU

東方數千年號稱古文明一大國如吾中華者,當然有甚多之國粹流傳於世間,而供教育者研究之資料也。雖然,東方國性,向多趨重貴族式,而罕為平民式者。其所謂文明事業,大抵依帝王士大夫為隆替;而閭巷田野間,農工商等之社會習尚,十九皆湮滅不傳。予甚感焉!繼而思吾國國粹,蓋偏重於文科藝術之研究,以其迫於貴族式也。若乎武術藝術。與平民社會諸藝術,均鮮列於國粹之價値矣。間嘗稽我國史,武派雖不少奇才異能;而但詳俠義,武術則略也。武科雖不少豐功偉績;而但著兵法,武術則缺也。若是乎中國果無武術之國粹乎?曰,否,否,蓋有之。則在江湖獻藝者之手技,或方外僧侶等之口授;若欲求諸學校教育,專科研究,以普及於平民智識者,闃然未之前聞。夫世間無論何事,皆自有其條理,皆可為藝術;為藝術,皆可成學科,而有其教材。况乎吾國武術,自有精義原理良法妙用存乎其中,卓然為我東方古文明國一大國粹。雖少專書傳世,然自有能之者學習而傳之。日本有柔術專家,蔚成武士道。歐洲古時有武士教育,今尤多技擊家。列强之名,有由來矣。今我國正患文弱,倘有武術家起而振奮之,寧非急務乎?吳君志靑,毅然倡設武術會;更本其夙所練習之武術智能,著為武術新教材。今付刊以廣供各學校之傳習,他日於普通體育科外,新樹一幟,斯已美矣!矧其裨益於平民教育,尤切實用歟?爰弁數語,以告武術學者。

新紀元之十年四月沈恩孚

For thousands of years, the “great civilization of the East” was our China. It has of course had a rich cultural influence upon the world and supplied educators with much to research. However, it is characteristic of our eastern nation to have typically emphasized things that happened to aristocrats and rarely to ordinary people, feeling that the history of a culture generally comes down to the rise and fall of emperors, kings, and generals. As for society at large in the lanes and fields, the experiences of farmers, laborers, and merchants have mostly been tossed aside, a loss which I deeply feel. When I think about our nation’s culture, I see that it has laid particular stress upon the study of literature and art precisely because it has been so obsessed with the nobility. Martial arts or any of the other skills of the common people have rarely been considered worthy of being classified among the essential aspects of our culture.

Examining into our nation’s history, although martial arts schools have many tales of people with astounding abilities, there is information about the heroes themselves but a lack of information about the actual skills they possessed, and likewise, although our military histories have many records of great achievements, there is information about the strategies used but a lack of information about the actual skills that the soldiers used to carry them out. Are martial arts therefore absent from China’s cultural essence? No, not at all. They are to be found in the exhibitions of itinerant performers or the teachings of mystical monks. But the hope that they might be made a part of educational curricula and become a field of study, the idea of spreading them until they are common knowledge among the people, is something that is previously unheard of.

Whatever people do, they develop a way of doing it, and thus it can become a craft. Once something is a craft, it can be turned into a course of study. And once something is made into a course of study, it will have its textbooks. This should be especially true for our nation’s martial arts, since they contain refined principles and sophisticated methods. They are an outstanding and grand feature of our ancient civilization. Although there are not many specialized books that have been passed down, there are nevertheless still capable people to pass on these teachings. Japan has its Judo masters to spread their culture of Bushido. Europe in the middle ages had its knights to set an example and now in modern times has its many skillful boxers. These are reasons why the great powers are considered “great”. Our nation is now in a state of anxiety and weakness. Is there not an urgent need for our martial arts masters to get up and inspire us?

Wu Zhiqing, determined to promote these arts, established the Martial Arts Association and has been using the knowledge he has accumulated on the subject to produce new teaching materials, such as this book which is soon to be published and then widely supplied to various educational institutions. Someday it will have spread beyond schools of physical education and stand as a proud banner for us all, for it can also serve as a very practical means of educating the masses as a whole. Therefore I have written these few words to tell martial arts students about it.

- Shen Enfu, April, 1921

–

林序

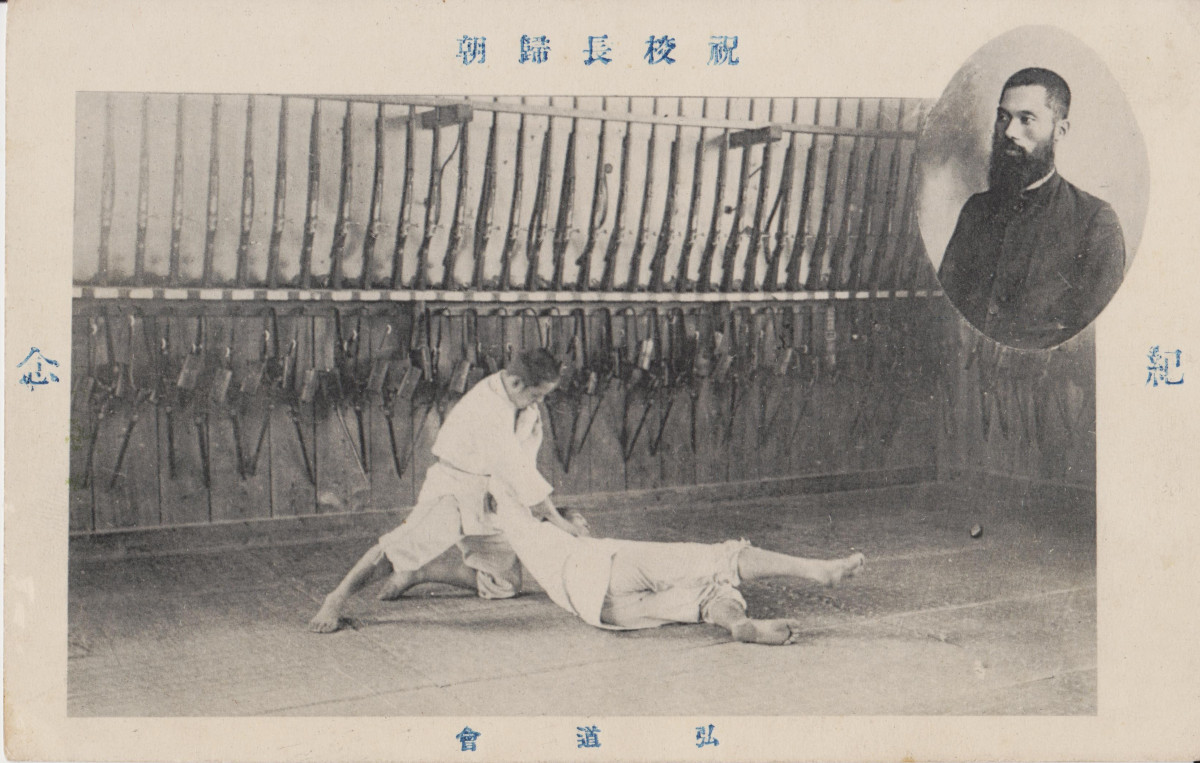

PREFACE BY LIN CHUANJIA

健全之精神,栖於健全之身體,身體不健,則精神昏惰,陷於醉生夢死,而不自知。中國自甲午一敗,睡獅始覺。余以化學生求試武備學堂。因身材短小,目力短視,不獲選。然丙申刱時務學堂,以幼學操身為體操教科,佐以中國易筋經。二十年來,南行不避煙瘴,北行不避冰霜,周遊十五省區,實賴此有用之身,精神不減也。黑龍江為尚武之地,愚夫婦十年教訓;今畢業生之武術,亦見稱於精武體育會,如劉生鳳池是也。然未若郭生濬黃,日馳馬八百里,挾五經以傳孔教於庫倫,尤勇敢也。嗟乎!南强北勝,海內紛紜。平心論之,滿蒙土厚水深,勢不可當,兵皆可用;成吉思汗征歐之偉烈,亦我五大民族之光也。願吳子鼓吹東南文明之學子,毅然自强,自此書始。並養精蓄銳,建設新事業。則體育之用於實業道德甚多,非僅以尚武耀兵也。不戢自焚,古有明訓。武裝和平,人皆可用。吾其師美利堅乎!

閩侯林傳甲謹序

A strong mind dwells in a strong body. When the body is not fit, the mind is not really awake. One slips into a befuddled lifestyle and loses self-awareness. Since our defeat in 1894 [1st Sino-Japanese War], our “sleeping tiger” of a nation began to stir, so I decided to join a military academy. But because my body is too small and I am too nearsighted, I was not accepted. In 1896, I instead established one of the Modernization Schools, where one thing that we taught to the children was physical education based on the Yijinjing exercises. For the last twenty years, I have not been able to avoid the suffocating humidity when traveling in the south or the biting frost when traveling in the north, and so while journeying through fifteen provinces [in his work as an educator, geographer, and historiographer], I have relied on such exercises to stay healthy and keep my mind sharp.

Heilongjiang is a place that still has respect for the martial quality. I taught there with my wife for ten years. I have recently graduated in a martial arts course at the famous Jingwu Athletic Association. However, I am more like a steadfast Liu Fengchi than a superhuman Guo Junhuang, who galloped his horse hundreds of miles in a day, as I carried the Five Classics [Book of Poems, Book of History, Book of Rites, Book of Changes, Spring & Autumn Annals] under my arm to pass on Confucian teachings in places like Ulaanbaatar, which takes a peculiar courage indeed.

The south struggled, but the north conquered, and everything in between is now a mix of cultures. Calmly put, Manchuria and Mongolia are vast territories that contain unstoppable peoples, soldiers always ready to fight. Such peoples enabled Genghis Khan’s conquests to spread all the way into Europe and are now the glory of our “five great ethnicities” [in top-down order on the Republican-era five-colored flag representing the five ethnic groups in China: Han Chinese (red), Manchus (yellow), Mongols (blue), Hui or Chinese Muslims (white), and Tibetans (black)].

I hope that Wu’s preachings will get students of southeastern Chinese culture to resolve upon self-strengthening, which starts with books like this. Build up your energy for the new tasks that lie ahead. Physical education has a great many uses in industry and ethics, and is not just for the military. Ancient lessons have taught us: “If you do not learn to control yourself, you will destroy yourself.” [paraphrasing from Zuo’s Commentary to the Spring & Autumn Annals, 4th year of Duke Yin: “An army is like fire. If it is not restrained, it will incinerate itself.”] But to be prepared for war during peacetime is better for everyone, as the Americans have shown us.

- sincerely written by Lin Chuanjia of Minhou County [in Fujian] [This preface is undated, but it was obviously written around the same time as the surrounding prefaces since Lin died in Jan, 1922.]

–

謝序

PREFACE BY XIE QIANGGONG

今之世界,科學世界也,科學之於世界,猶腦筋之於人身。無腦筋,則人身無精神;無科學,則世界無文明。故今日莊嚴燦爛之世界之新文明,實則精密佳妙之科學之現象也,科學之部類,無分乎文武,今世陋俗,執有文學無武學之說,是謬見也。夫立國大地,文武不可偏廢。故所謂武術,亦新文明之一種原素也;亦可曰一種科學也,豈徒以技藝名之乎?且卽為技藝,亦豈可無科學之原理原則乎?我中華為世界有名之古文明國,在昔帝王時代,開國創業,競尚武功。斯時講武術者,因帝王習尚,播為世界風俗;而武術家輩出,武術書紛陳,是科不無進步。迨乎國家承平,修文偃武,民風日趨文弱;不數十年,武術界不絕如縷,廢弛不復講求。蓋社會之智識,純隨帝王嗜好為轉移,數千年如出一轍,良可慨歎!歐洲當中古封建時代,諸王侯各養武士,尚技勇,武術因之日精。其後封建廢而武士屛棄,武術漸衰,中外蓋有同慨!雖然,我國之武術,遺傳於後世,而得為寶貴之一種國粹者,蓋亦不少,日本得我緒餘,別成一種武士道。維新以後,參加科學之精意,遂以技擊為戰勝强俄之特別利器,亦可謂殊榮矣!返觀吾國武術,雖有南北少林武當等派,然而有保守,無進步,不能利用之以增國防之色彩;此其故何也?蓋無專科研究之組織,卽不可合於科學之方法。是故徒事拘墟,而不能普及發展耳,吳君志靑,首創武術會於海上,成立僅及年餘,會員日增;分會且推及於閩粵南洋,遠及法國等處;前途蓋有無窮之希望焉。吳君於武術專門研究有年,其言曰:武術蓋與科學有密切之關係者也。居今日而謀救國,武術實為要圖。然苟不依科學之方式,以改良推廣之,則永無進化之日。其研究武術之大略:(一)須按生理學之義理,而不背衞生之要旨。(二)從心理上研究,求學者之智識如何精確,意志如何高尚,感情如何活潑輔以音樂,助學者之興趣。(三)須合於教育上之程序,而養成是科人才,謀普及於平民社會。(四)練習各種動作,須合實用,如交際上跳舞諸有規則之優美運動;以期改良社會粗野之習慣,而以體育輔佐德育精神,養成完全高尚之人格。綜上四者,以立武術研究之要旨;謂之武術科學可也,謂之科學武術亦可也。夫如是,是科之價値,庶幾可增高於今日競存之世界矣。今吳君又以其所研究貢獻於世而按生理之構成,與體育之原理,心理之關係,教育之順序,以編成各種柔軟體操,分之,則為精練優勝之各種新式技能;合之,則連成一貫之實用手法;狹之,則交際社會,為活潑優美之舞蹈;廣之,則捍衞國家,為出奇制勝之利器。嗟乎!中國武士道,曷嘗非新文化運動之一種乎?世有倡武術救國者,須知仍是科學救國而已。故惟有科學之武術,始足稱武術;亦始足發揮光大科學之效用也。今吳君將以斯編付刊,廣供各界之傳習。爰序其要略於簡端。

中華民國開國十年四月强公謝燮

The modern world is a scientific world. Science in the world is like the brain in the body. Without a brain, the body would have no mind. Without science, the world would not have a civilization. The majestic and magnificent world of modern civilization is indeed built upon precise and ingenious use of scientific phenomena. However, science does not categorize things into “civil” or “martial”. It is ordinary people who cling to dubious notions of civil knowledge versus martial knowledge. Because founding a nation over such a huge territory cannot be achieved by relying on either the civil or martial quality on its own, martial arts have to be equally considered to be an element of modern civilization. Martial arts can also be considered to be a science and not merely an “art”. How indeed can any skill not involve scientific principles?

Our Chinese nation is famous throughout the world for its ancient civilization. In the days of emperors and kings, the pioneering work of founding a state was still a military endeavor. At such a time, martial arts practitioners were favored by rulers and this had an influence on the culture of the society. More martial arts experts emerged and more martial arts texts appeared, and so the science progressed. But when the nation was at peace, it turned to civil matters and abandoned military concerns, and then its people increasingly weakened. After just a few decades, the martial arts community was reduced to a precarious existence, on the edge on being forgotten. For thousands of years, our society’s customs and knowledge shifted according to the whims of its rulers, something that gives us cause to sigh with regret.

Similarly, the nobles of Europe in the Middle Ages all supported knights and had respect for skillful warriors, and so their martial arts became more and more refined. When feudalism later ended, the knights disappeared with it, and the martial culture of Europe gradually declined. Thus both China and foreign nations face the same sense of having lost something.

However, our nation’s martial arts were passed down to future generations and treated like cultural heirlooms. (Because there were so many, Japan took from the surplus of our martial arts to create their Bushido. After embarking on their period of modernization, they added scientific knowledge to their arsenal and then used their skills to defeat Russia, even with all her specialized weapons, surely a glorious achievement.) Looking over our nation’s martial arts, although styles classified as “northern” or “southern”, “Shaolin” or “Wudang”, have been preserved, they have not progressed. They therefore cannot be used to add to our national defense. Why? Because unless they are organized into a specialized system of study, they will not conform to a scientific methodology. If we are narrow-mindedly fixated on one style or another, our martial arts as a whole cannot be popularized and further developed.

Wu Zhiqing founded the Martial Arts Association in Shanghai, just over a year ago, but its membership has since increased to such an extent that branch schools have spread south into Fujian and Guangdong, and even as far away as France. Its future has limitless prospects. Wu has made a specialized study of martial arts for many years and asserts that martial arts are intimately related to science. “The plan is to rescue the nation, and martial arts are the key to that plan. But if we do not rely on scientific means to improve and popularize these arts, we will never make any progress toward that goal.” His general plan for the studying of martial arts runs thus:

1. It has to be in accordance with physiological principles and not go against the requirements of health.

2. It should follow a psychological approach, seeking for the student’s knowledge to be accurate, ambitions to be noble, and emotional state to be lively. A musical rhythm can also be used as a means to help the student feel more engaged in the exercise.

3. It has to be structured in a pedagogical sequence, in order to best cultivate the talents of individuals and be spread more efficiently to the rest of society.

4. The training has to have a similar function to the rules of graceful dance, that of reforming the cruder habits of society, of boosting one’s moral instinct and elevating one’s character.

Equipped with these four points to ground martial arts research, it can be called “martial arts science” or “scientific martial arts”. In this way, it is a valuable branch of study that can give us an edge in this modern competitive world. Wu is now offering what he has learned to the world, using principles of physiology and sports training, a psychological approach, and a pedagogical structure to make a series of calisthenic exercises. Any one of these exercises is a simple yet superior means of developing skill. When combined, they are a continuous series of practical hand techniques. Looked at with a narrow view, it serves as a lively and graceful dance which facilitates social interaction. Looked at with a broader view, it is a cunning weapon for defending the nation. Here then is Chinese Bushido. How could exercises like these not be a feature of our New Culture Movement?

Those who promote martial arts to rescue the nation have to understand that they also need science in order to rescue the nation. Therefore it is the more scientific martial arts that deserve to be considered the real martial arts, and they are also the ones that reveal the wonderful effectiveness of science. Wu is about to send this book to the printers in order to spread the knowledge it contains to a wide audience. Thus I have written this preface to supply a brief overview.

- written by Xie Qianggong, April, 1921

–

唐序

PREFACE BY TANG XINYU

世界無新物,特本諸原質,各盡發明製造之能事而已;世界無新理,特本諸自然,各盡尋繹推演之心力而已,故一代之技能,有一代之應用;一國之技能,有一國之特性;古代之技能,不必適用於今界;歐美之技能,未必適用於中國;因環境之不同,而思想之各異也,吾於體操亦然,德日之體操,重强健身體而適用於軍事;英美則重訓練精神而適用於生活,雖其方法應用各有不同,要皆本諸其固有之活動,適應各自之環境,以發揮其特性而已,不知者妄行採取,徒為削足適屨之謀,未見截長補短之效,尤有復古者流,斤斤為國粹之保存,而昧於時代環境與思想之變遷,是皆不能盡發明製造之能事,與尋繹推演之心力者也。

吾國民固自有其技能,特時代應用之不同,未免相形見絀耳,吾國又固有其特性,特訓練之法不良,故未足以發展耳,試放眼觀察現代之環境,旣不應具黷武雄心,如德日之專重軍備;又不可泰然自處,如英美之偏重生活,則吾國現代所取之體育方針,應折衷此二者,已無疑矣。吾國固有之技能為何?武術是也。固有之特性為何?仁義是也。之二者,如能加以變通採為體育之方法與目的,更善事應用訓練,以應付現代之環境,必能折衷德日英美之間,而吾國民有卓立之地位也。

吾友吳君。素精武術,尤明體育之眞義;故本其平日所學,參以教授心得。以中國固有之武術為原質,加以科學方法之製造,發明一體育上之新物品,命其名曰「應用武術中國新體操」今更名「科學化的國術」旣成此册,索序於余;余細玩其編列之次序,與應用之方法,深合生理學心理學及教育學之原理,旣足增進健康,又能引起興趣,更能養成各善良之性質,是誠體育研究之菁華,尤預備應付環境之良術也,謹弁數言,質之識者以為何如?

中華民國十年四月唐新雨

There is really nothing new in the world, everything being built from fundamental elements, and thus inventions come simply from skillfully putting those elements together. There are also really no new truths in the world, everything being derived from fundamental principles of nature, and thus insights emerge simply through persistently applying powers of deduction. And therefore the skills of a particular era will serve the needs of that era and the skills of a particular nation will be characteristic to that nation.

Ancient skills are not necessarily suitable for the modern world. European and American skills are not necessarily suitable for China. Different circumstances bring different ideas. The same is true for our forms of exercise. German and Japanese calisthenics emphasize strengthening the body for military use, whereas British and American calisthenics emphasize boosting the spirit to make better workers. Although their methods serve different purposes, they are each based on their nation’s innate patterns of exercise, suitable for each nation’s particular circumstances, and express the character of that nation.

Ignorant people choose any form of exercise, giving no thought to whether it is appropriate. They are following a strategy of “whittling the foot to fit the shoe”, not noticing the effects of trying to bring equality to one’s shortcomings by way of reducing one’s strengths. And then there are those who seek to return to the past in every little detail in order to preserve our national culture. They fail to understand that circumstances and ideas change over time. In both cases, such people lack skills of invention and powers of deduction.

Our nation’s people have an innate skill, which is not as good as it used to be even though its use has varied from one era to another. Our nation’s people also have an innate character, which will not get developed if the training is not right. Looking at the wider view of our situation in modern times, we should not be too militaristic, like Germany and Japan focusing on training their armies, but we should also not be too sanguine, like Britain and America putting their attention simply on the people being able to make their livelihood. The guiding principle of the physical education we choose for our nation should undoubtedly be somewhere between the two.

What is our nation’s innate skill? Our martial arts. What is our nation’s innate character? Benevolence and righteousness. If we can take our innate skill and our innate character and adapt them for modern times, then we can pick the right methods of physical education most suitable for our goals, and by adding in the best forms of training, we will able to respond to our present situation. We have to get the right mix of the emphasis of Germany and Japan with the emphasis of Britain and America [i.e. training for both fighting and health], and then our nation will be able to stand tall in the world.

My colleague Wu is an expert at martial arts, and particularly understands the true significance of physical education. Therefore based on what he has learned from his own training and what he has discovered through teaching it, he has taken China’s native martial arts and added scientific methods to create a new form of physical education, which he put into a book called Using Martial Arts to Make China’s New Calisthenics, the title recently changed to Scientific Martial Arts. Once the manuscript was completed, he asked me for a preface.

I have carefully gone through his arrangement of exercises and methods of applying them, and have found that they strongly conform to principles of physiology, psychology, and pedagogy. They are more than adequate for increasing health, and can enhance one’s sense of enjoyment, as well as cultivate good character. It is truly the height of physical education studies and is an especially good means for preparing us to deal with whatever situations might arise. I sincerely offer these few words, though I am sure that more knowledgeable people can put it better than I have.

- Tang Xinyu, April, 1921

–

蔡序

PREFACE BY CAI JUEZAI

我國武術,歷久不敗,蓋有哲理存乎其間,非精於斯道者,實難洞悉之也。其後派別旣夥,眞傳漸失,所以然者,一則挾技橫行,致遭社會唾棄;一則智識譾陋,不知其所以然,而失其眞;良可惜已。歙縣吳君志靑余同學也,研究武術十有餘稔,教授之暇,輒自練習,其好學不倦之心,令人肅然起敬,民國八年,吳君集合同志,刱辦中華武術會於滬南,不期年而會員已達千餘人之多,深受社會信用,乃者出其所學,著成一籍,題曰「應用武術中國新體操」今更名「科學化的國術」。改進武術,意在普及,一般學校社會咸可採用練習,謂為健身法可;謂為延生術亦無不可,造福人羣,實非淺鮮,武術前途,有曙光矣!謹為序。

中華民國十年四月蔡倔哉

Our nation’s martial arts have never been outclassed, and this is because they are imbued with philosophical principles. Without fully mastering an art, it is truly difficult to understand it thoroughly. As systems later diverged into styles, authentic teachings were lost. This is on one hand because practitioners who misused their skills were expelled from society, and on the other hand because practitioners who had an incomplete knowledge of the art did not have a thorough understanding of how it worked and so were not able to pass on the true teachings. This is truly a pity.

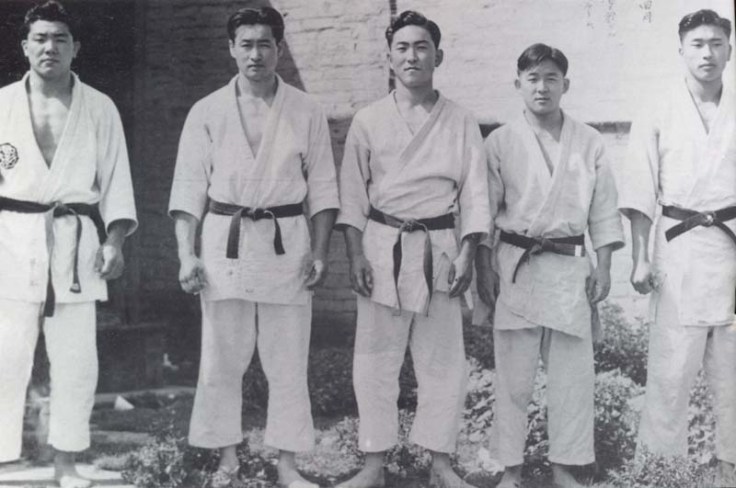

My fellow student Wu Zhiqing of She County [in Anhui] has studied martial arts for more than ten years. In teaching and training, his tireless love of learning has earned him great respect from people. In 1919, Wu gathered together his comrades to establish the Chinese Martial Arts Association in the southern part of Shanghai. After not even a year had gone by, membership had already risen to more than a thousand people.

Having garnered such deep regard from society, he in return has drawn from his learning to write a book which he originally titled Using Martial Arts to Make China’s New Calisthenics, the title now changed to Scientific Martial Arts. He wishes to make martial arts easier to popularize, something that can be practiced in ordinary schools. These arts can also be thought of as both a method of fitness and a means of longevity, and so the benefit this would bring to people would by no means be insignificant. Because this gives us real hope for the future of martial arts, I sincerely write this preface.

- Cai Juezai, April, 1921

–

凡例

GENERAL COMMENTS

一本書以普及體育為主旨,故取材極簡,期合實用而便練習,編者曾實驗於上海女靑年會體育師範民立中學江蘇省立第二師範上海縣立一高養正潮惠和安第二師範附屬育材等學校,及江蘇省教育會體育研究會曁中華武術會等處,已獲良好效果。

– The purpose of this book is to popularize physical education, and therefore I have selected material that is extremely straightforward and which is both practical and easy to practice. I have experimented with this material in the Shanghai YWCA Teacher-Training School, the Establish-the-People High School, the Jiangsu 2nd Teacher-Training School, Shanghai County 1st College, Municipal Uniformed Elementary School, Spreading Benevolence Elementary School, Harmony & Peace Elementary School, 2nd Teacher-Training Attached School, and the Raising Talent Elementary School, as well as the Jiangsu Educational Association, the Physical Education Research Association, and of course the Chinese Martial Arts Association, and have in each case obtained excellent results.

一本書採取各家國術菁華依據生理學心理學教育學等之原理,變成動作,雖不敢謂完善,然按諸科學尚無背謬,故定名曰科學化的國術。

– For this book, I have selected from the best exercises from various styles of Chinese martial arts and adjusted the movements in accordance with principles of physiology, psychology, and pedagogy. I would not dare to claim that these exercises are perfect, but they are all on the side of the realistic rather than the absurd, which is why I have called the book Scientific Martial Arts.

一本書適合高小及普通師範學校教材;卽個人家庭,能依法練習,可免腦肺胃腸等病,而入於健康之域。

– The material in this book is suitable for use in high schools and teacher-training schools. People in individual households can also use it to practice, and thereby become free of ailments of the brain, lungs, intestines, and so on, and enter into a state of better health.

一本書除詳細說明外,附以銅板製成各種姿勢圖;俾學者按圖練習,一目暸然,無困難扞格之弊。

– Beyond the detailed explanations, there are also photos of each posture in order for you to more clearly understand how to practice these exercises, free from any frustrating confusion.

一本書分上中下三編:以第一部為上編,第二第三部為中編,以第四部為下編,除上編先行付梓外,中下三編正在實驗中,一得圓滿效果,當續出版,

– The plan is to divide this material into four parts over three volumes, part one in the first, parts two and three in the second, and part four in the third. Apart from this first volume being ready to go to the printers, the later volumes still need work. Once I am fully satisfied with the results, they will then be published. [The later volumes were apparently never produced, perhaps indicating that Wu had ended up unsatisfied with them after all, or possibly the interruption of such work due to his several years of military service during the 1920s drained the momentum for this particular project. Whatever the case, part one was considered important enough on its own to be republished in 1930.]

–

緒論

INTRODUCTION

人類進化,有天演之公式:合則生存;否則敗亡耳。我中華立國四千餘年,其間他國之滅國亡種者,不知凡幾;而我國卒未至於淪胥者,要必有足以自存之道焉,自存之道何在?蓋一則以文化之燦爛,一則以武事之發揚,而近者文化方有日新之機,武事則如江河日下;至可慨已!志靑不揣譾陋,前創辦中華武術會於滬上。藉謀集合同志,研究國粹,以期保存與發展焉。尤有感者,今昔時勢不同,現為文化進步,科學劇戰時代,故國術一道,脫不以科學方法,從而改進,勢難邀社會之信用,必致完全失傳,而國運亦將受其影響矣。茲將國術與生理心理教育等之關係,分述如下:

Mankind developed according to the laws of evolution. Conforming to those laws brought survival and defying those laws brought death. Our Chinese nation was founded more than four thousand years ago. Within that time, so many nations have perished, their people vanquished, that I cannot even place a number to it. But our nation has not disappeared because we have had sufficient means of self-preservation. And what are these means? The magnificence of our culture and the development of our military. But alas, in modern times our culture has been affected by so many new inventions and our military has slipped into constant decline.

Despite my shallow abilities, I founded the Chinese Martial Arts Association in Shanghai in order to gather my comrades and do research into our cultural essence, hoping to preserve these arts and develop them further. I strongly feel that our modern situation is not the same as it was in earlier times. We are now in an era of cultural progress and scientific competition. Martial arts training has failed to make use of a scientific approach and yet can be greatly improved by it. Although it may be difficult to convince society of this, the outcome could otherwise be that these arts will end up being lost altogether, and that would have a terrible effect on the future of our nation.

I will now touch upon how physiology, psychology, and pedagogy are relevant to martial arts, addressing each of these things below:

(一)國術與生理之關係

1. The Relationship Between Martial Arts & Physiology:

人皆欲享幸福者,天性然也。然一切幸福,皆本於身體生活之健全,凡人不求幸福則已;苟欲求之,不可不依據生理學,力圖身體生活之健全,明矣,語云:「戶樞不蠧;流水不腐」;人生於世,自當及時運動,運動之於人身,其重要與衣食住等,衣食住一日不可少,而運動亦一日不可缺也。蓋人生職業之興敗,當視精神與體力之何如為比例差,而精神之所以能充分,體力之所以能健强者;皆由鍛鍊而得,故吾人一日內,除經營職業外,當有一定之時間,修養其身體與精神;以為職業上之補助,且於經濟上亦有極大關係,蓋體力强健,精神充足,旣無疾病之苦痛,又無醫藥之消費;職業昌隆,經濟裕如,誠為人生無上之幸福也已。

Everyone seeks happiness. This is only natural. But every kind of happiness is rooted in the health of the body. If you do not seek happiness, then never mind. But if you do seek it, it is entirely dependent on physiology, and so clearly it is a matter of striving for physical health. A saying goes [from Master Lü’s Spring & Autumn Annals, book 3, chapter 2]: “Running water never goes stale and a door that gets used does not get rusty hinges.” One’s life naturally requires exercise. Exercising the body is just as important as being clothed and fed. One cannot go without clothes and food for a single day, and one also cannot go without exercise for a single day.

To be successful in one’s career equally requires a good attitude and physical stamina. Both a full spirit and a strong body will be obtained through exercise. Therefore within a given day, beyond just going to work, there has to be time set aside to cultivate body and spirit. This will not only make you even better at performing your job, it will thereby also have a huge effect on your financial situation. This is because with a healthy body and full spirit, you will not suffer from any illness, and thus you will not need to buy any medicines. Therefore you will prosper at work and save money at home. Surely there is no higher happiness in life.

(二)國術與心理之關係

2. The Relationship Between Martial Arts & Psychology:

武術者,體育上之一種實用運動也。蓋運動之事,如祇有學理之價値,而無應用之價値,對於心理上,朝於斯,夕於斯,漸致厭倦不樂,必難得美滿之效果,又豈非一大缺憾乎?故國術除求衞生外,尚有防禦危侮之意,存乎其中,卽如體操中之足球籃球等運動,亦另有一種競勝心理,使人不厭反復練習,以達所爭目的而後已也,編者歷年教授體操,為欲防學者厭倦之心,每次必變動教材,色色翻新;非然者,卽不能使人增加興趣,樂於學習也。若教之以國術,亦有不熟不止之勢,其所以不厭倦者,以其能達他種應用之目的;天下惟有實用者,為能得人心理上之欣羨,此其關係視僅求衞生者為何如乎?是故國術運動為一種實用之體育,亦卽一種實用之心理也。

Martial arts are a very practical form of physical exercise. If an exercise only has value in principle and not in reality, your attitude toward it with each passing day and night will change, gradually finding it to be tedious and uninteresting, and it will be difficult to get any enjoyment out of it. Is this not an enormous flaw? Beyond bringing health, martial arts are also intended for self-defense. Sports such as soccer or basketball have a competitive mentality, which causes people to never tire of repetitive practice because they are working toward winning games.

Throughout my years of experience of teaching exercise, I have tried to find ways to prevent students from getting bored, and so every time I teach a lesson I make adjustments to the material, bringing some variety, keeping it fresh. If I do not do this, I cannot get the students to increase their interest and find pleasure in what they are learning. In the case of teaching martial arts, the training has a quality of never being finished. The reason it does not become boring is because it is working toward a goal. When something has real-world application, it is easy for people to admire it. Would people feel this way if it was only for health? Therefore martial arts are a practical form of physical education and appeals to our sense of wanting things to be useful.

(三)國術與教育之關係

3. The Relationship Between Martial Arts & Pedagogy:

吾人吸收智識,必得有腦力,精神,體力三者,然三者之中,而尤以體力為要;蓋精神腦力,悉由鍛鍊而得也,人類以共同為生活,智識單簡,尚可謀生;體力不健,自絕生存之道也,故鍛鍊體軀,實為教育上之大助。夫國術以拳術為主,拳術為我國獨有之國技,運動平均,少長咸宜,非其他之體操法可同日語也。旣能鍛鍊體軀,又能活潑精神;且合實用,小則防身,大則保國,為個人團體之保障,戰鬭時短兵相接,非熟於斯道者,決難取勝。故武術所以練習手眼身步法,運用心身之聯合,發揮個性之本能,養成耐勞判斷注意有恆諸德性,增進記憶力,助長其天良之義勇,負互助之責任,為教育上之重要關鍵,為人類生活上之必修科學。

To absorb knowledge, we need to have three things: intelligence, spirit, and health. But among these three things, health is the most important. Spirit and intelligence can thereafter be obtained through training. Human beings make a living as a group, and so even a simple level of knowledge is enough to make a living [because gaps in knowledge are compensated for by others in the group specializing in and carrying out other necessary tasks]. But if you do not keep your body healthy, you are cutting yourself off from this means of surviving [by being unable to serve a useful role that contributes to the group]. Therefore training the body is of the greatest help in teaching students.

Our martial arts emphasize boxing arts. Our boxing arts are our nation’s special skill. They exercise the whole body evenly and are thus suitable for young and old alike. No other methods of exercise deserve to spoken of in the same breath. These arts can train your body and liven your spirit. They also have a dual function: on the small scale, they can defend the body, and on the large scale, they can protect the nation. They serve to safeguard both the individual and the group. To engage in close-quarter combat without skill in these arts would make victory very hard to achieve.

Martial arts therefore train methods of hand, eye, body, and step. They work both mind and body in tandem, and develop one’s natural instincts. They cultivate the qualities of hard work, determination, focus, and perseverance, as well as enhance memory and help build one’s sense of morality and duty. All of these qualities are keys to education and are things that human beings need to learn in order to survive.

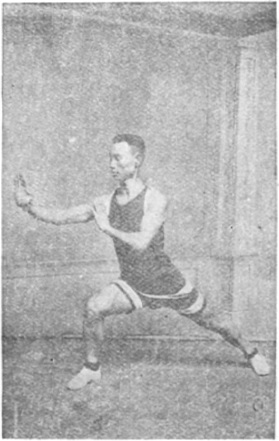

志靑不敏,謹就上述數種關係,本吾國固有之國粹及數載施教實驗所得,編成「應用武術中國新體操」今復與△△商榷改良修正,更名曰「科學化的國術」,所謂科學化的國術者,卽以科學方法,改進國術,使合乎生理心理,教育諸原則,以期切合於實用,而易普及之謂也。凡分四部,合之則成一套國粹之武術;析之則為實用之手法;因之則為出奇制勝之技能,變之則為活潑優美一種舞蹈之動作;若更和以音樂,則心身修養;裨益不尠,惟謬誤之處,在所不免;尚祈海內同志,進而教之。

I am not highly intelligent, but I have written the above explanations with sincerity. Based on our nation’s innate cultural essence and what I have discovered through the course of teaching it for several years, I have written Using Martial Arts to Make China’s New Calisthenics, but after some discussion, I have decided to change it to Scientific Martial Arts, which instead means to use scientific methods to improve our martial arts, to get them to better conform to principles of physiology, psychology, and pedagogy in hopes of making them more practical and easier to popularize.

This material is to be divided into four parts: [part 1] a combined set of martial arts exercises [the subject of this book], [part 2] an analysis of the functions of the hand techniques, [part 3] explanations for using these skills to ingeniously defeat opponents, [part 4] adjusting the exercises into a more lively and graceful dance-like series of movements by the addition of using musical instruments to create a metronome effect for them, thereby cultivating both mind and body simultaneously. [Parts 2–4 unfortunately exist in concept only. We can speculate that the reasons for this might have been that the first part was probably all that was needed to popularize these exercises among educational institutions, that parts two and three might have been of interest only to martial enthusiasts, and part four was perhaps unnecessarily eclectic.] The benefits of these exercises will not be meager, but inevitably I have made some errors. I hope my comrades throughout the nation will come forward and instruct me.

–

科學化的國術

SCIENTIFIC MARTIAL ARTS

第一部

PART ONE

第一節 四肢運動(兼有腰部之動作)

Section 1: AN EXERCISE FOR THE FOUR LIMBS (which also works the waist area)

種類

Type of exercise:

行進四肢與轉體之動作。

This is a method of advancing involving movements of all of the limbs and turning around.

術名

Name of the technique:

閃轉用掌循行進退。

SUDDENLY TURNING AROUND WIELDING PALMS WHILE ADVANCING & RETREATING

實用要訣

Keys to the exercise:

要旨係練習手眼身步法。為前後受敵衝前閃後掩護之基礎。由衝打掛護步隨身進。可以脫險謂之閃。由閃而欲制勝於人。必須復轉而實用打劈之術。轉則務將全身掩護。旋轉神速。始能盡閃轉之妙。此為脫險出奇制勝。相機因應之要法也。

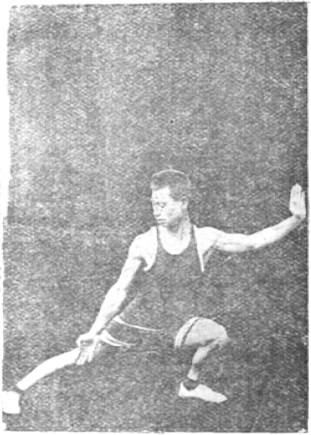

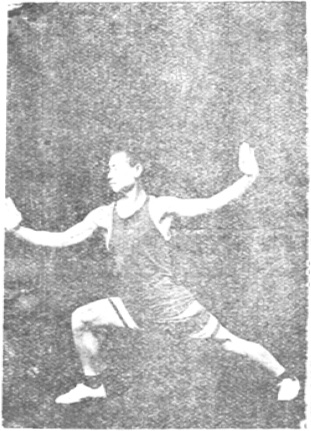

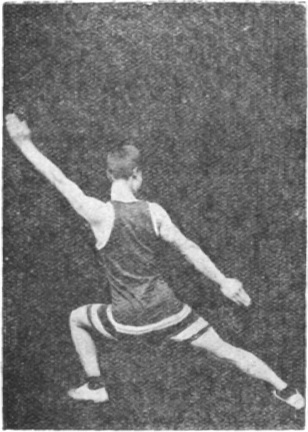

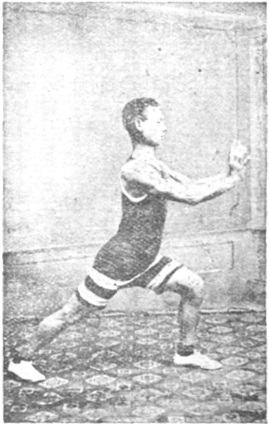

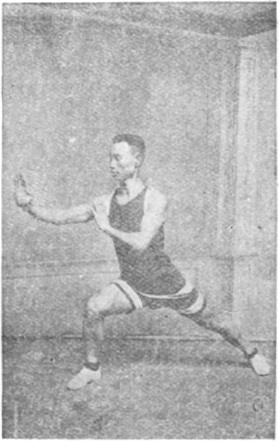

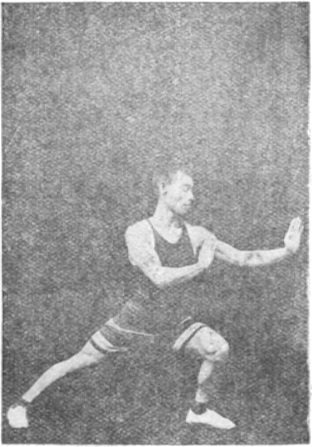

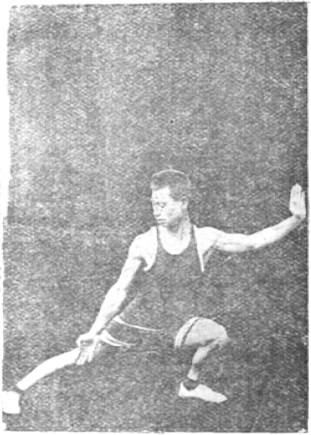

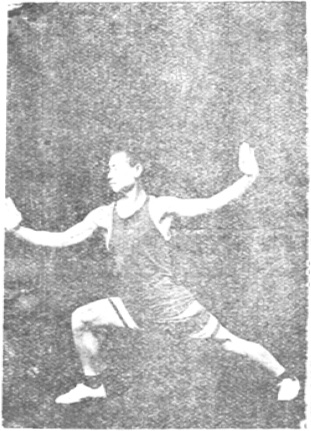

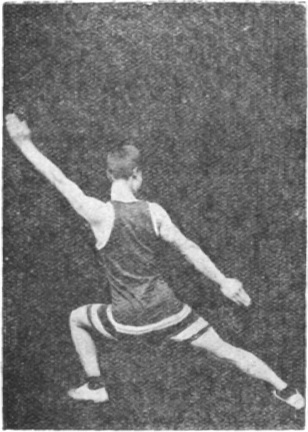

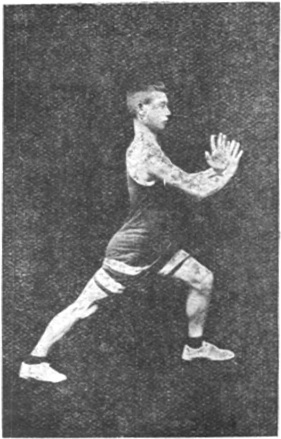

The main idea is to train methods of hand, eye, body, and step. This is basically a scenario of dealing with opponents attacking in front and behind, of striking at the one in front of you and then dodging around behind the other. After striking to one [photo 2], carry upward and use a covering step to advance toward the other [photos 3–5], and then you will be able to dodge around the danger presented by him [photo 6]. Once you are dodging, if you want to take control and subdue this opponent, you must then turn around and attack him with a chop [photos 7 & 8]. When turning, you have to shield your whole body by turning very quickly, and thus you will be dodging more effectively. This is an example of avoiding danger and defeating an opponent with an unexpected maneuver, a crucial principle in dealing with such situations.

實習動作

Practice method:

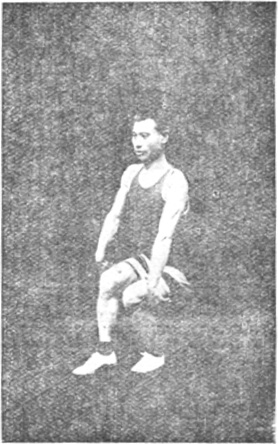

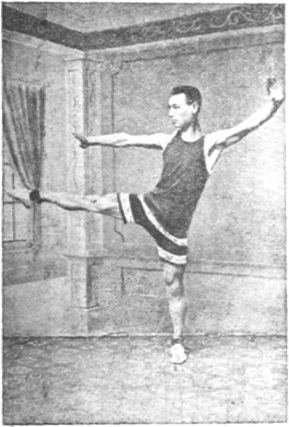

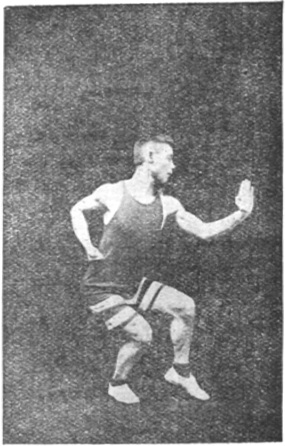

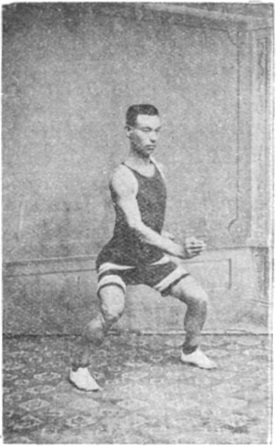

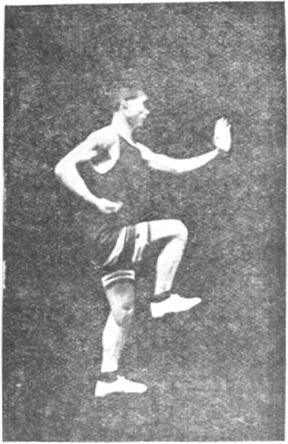

左式預備圖

Preparation posture on the left side:

立正抱肘式。眼平視。胸挺起。腰直。腿倂。兩腳約距離六十度。兩拳置於腰間。兩肘向後。如上圖。

Stand at attention with your elbows wrapped back, your gaze level. Your chest is sticking out, your torso upright. Your legs are together, your feet spread to make a sixty degree angle. Your fists are placed at your waist, your elbows pointing behind. See photo 1.1a:

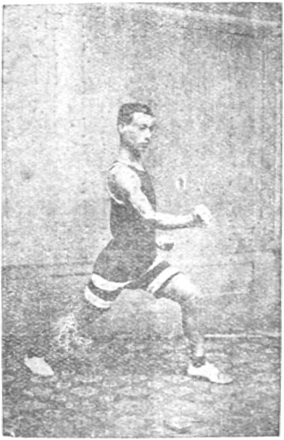

一、左拳變掌。由腰間向上經額前往右肩前下按至右腋。眼平視如第一圖。

1. Your left fist becomes a palm, rises from your waist, passes in front of your forehead, goes in front of your right shoulder, and pushes down until in front of your right armpit. Your gaze is level. See photo 1.1b:

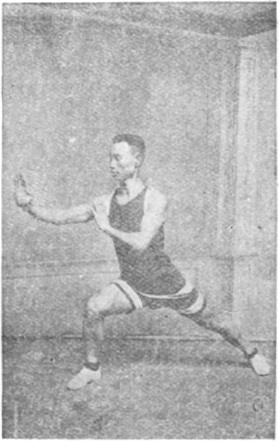

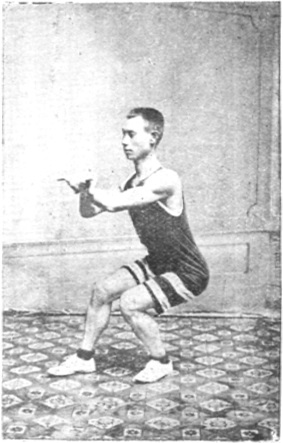

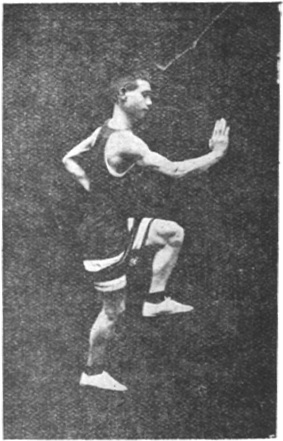

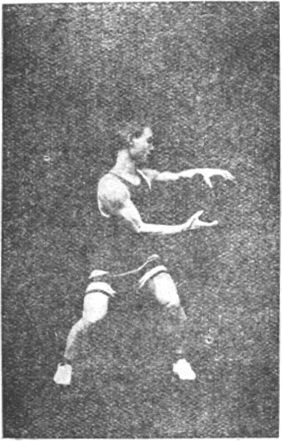

二、是時右拳卽變掌。由右腋下經左掌上穿出。向右伸直。手指向上。五指倂齊。掌邊向右。左掌貼右肩。掌心向內。掌形似柳葉。名曰柳葉掌。眼視右掌。身體順勢稍右轉。同時卽伸左腿。右膝曲為九十度。全身重量坐於右腿上。如第二圖。

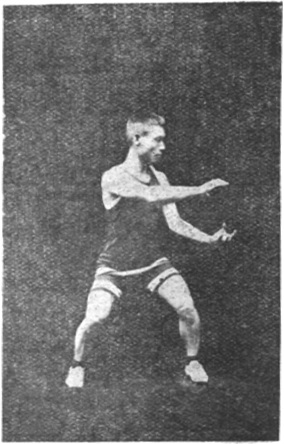

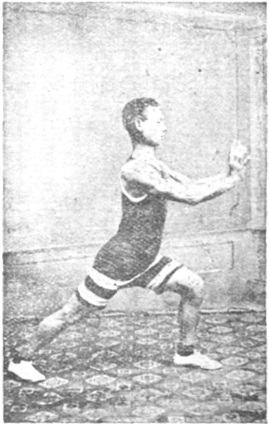

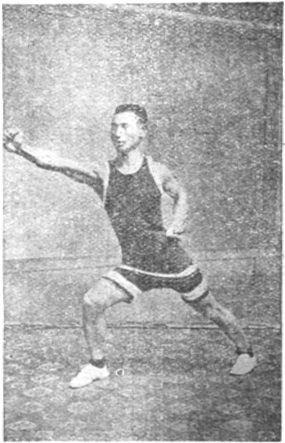

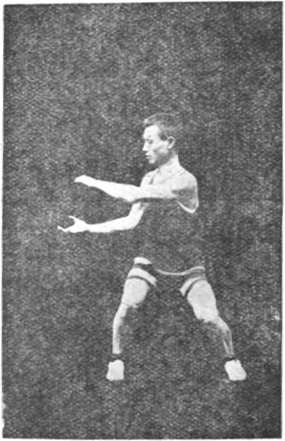

2. Then your right fist becomes a palm and goes from your right armpit, threading out over your left palm, and extending to the right, the fingers pointing upward, fingers together, the palm edge facing to the right, your left palm near your right shoulder with the center of the hand facing inward. Each palm is making a shape like a willow leaf, and thus it is called a “willow leaf” palm. Your gaze is toward your right palm. Your torso goes along with the movement by turning slightly to the right and your left leg extends [to the left], your right knee bending to make a ninety degree angle, the weight sitting onto your right leg. See photo 1.2:

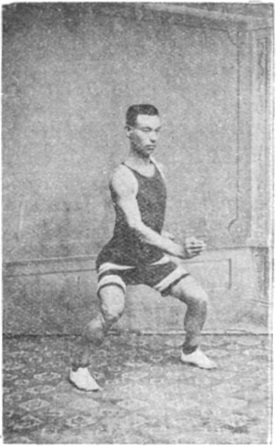

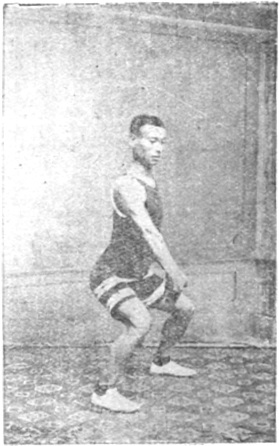

三、左掌由右肩向左伸直。指端向下。掌背近左腿。身稍左轉。眼視左掌。如第三圖。

3. Your left palm goes from your right shoulder and extends to the left, the fingers pointing downward, the back of the palm near your left leg, as your torso slightly turns to the left. Your gaze is toward your left palm. See photo 1.3:

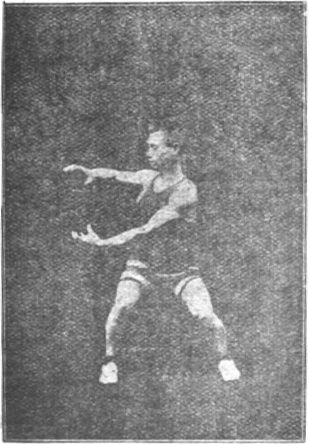

四、是時左掌沿腿上挑。卽彎左腿伸右腿。左腰亦卽同時伸縮。身體順勢稍左轉。左掌指端與鼻齊。右掌指端與頭頂齊。兩肘內扣。眼視左掌。兩臂形似扁擔。名曰扁擔式柳葉掌。如第四圖。

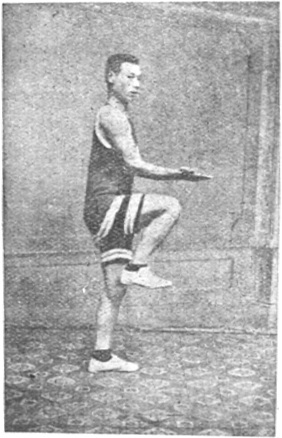

4. Your left palm passes along your [left] leg and carries upward as your left leg bends and your right leg straightens, the left side of your waist stretching, and your torso goes along with the movement by turning slightly to the left. Your left fingertips are at nose level, your right fingertips at headtop level, and your elbows are covering inward. Your gaze is toward your left palm. Your arms look as though they are carrying a shoulder pole, and thus this posture is described as “carrying a pole with willow-leaf palms”. See photo 1.4:

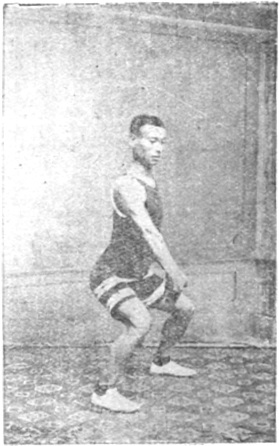

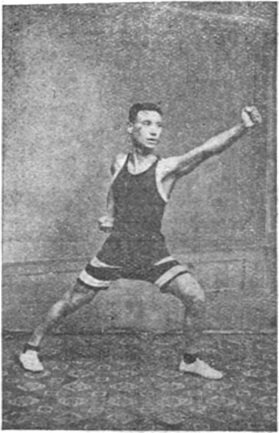

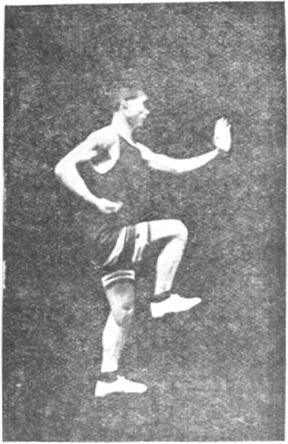

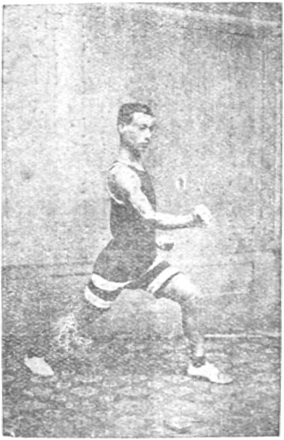

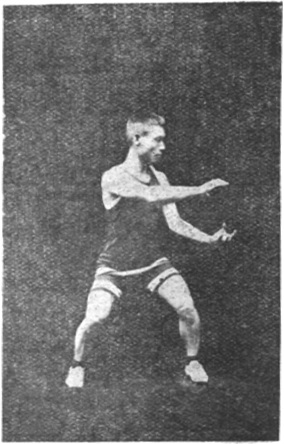

五、左掌上衝。右掌下掛。同時右腿隨右臂前上一步。身體順右腿猛閃向前。右腳趾點地成丁式。眼平視。如第五圖。

5. Your left palm thrusts upward as your right palm hangs downward. At the same time, your right leg goes along with your right arm by stepping forward, your body correspondingly going suddenly forward, your right toes touching the ground, making a T-shaped stance. Your gaze is level. See photo 1.5:

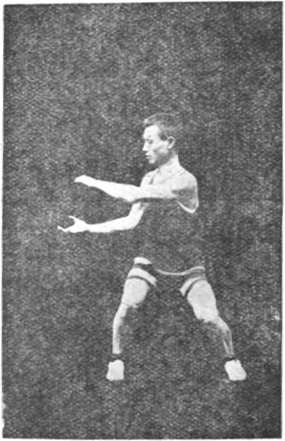

六、同時身體由左後轉。是時右腳再向前一大步。右腿下彎。左腳伸直。身體順右腿閃向左。同時左掌後劈。右掌前挑。眼視左掌。如第六圖。

6. Then your torso turns to the left rear as your right foot takes a large step forward, the leg bending, your left leg straightening, your torso lining up with your right leg as you dodge your left side away. At the same time, your left palm chops to the rear, your right palm carrying in front. Your gaze is toward your left palm. See photo 1.6:

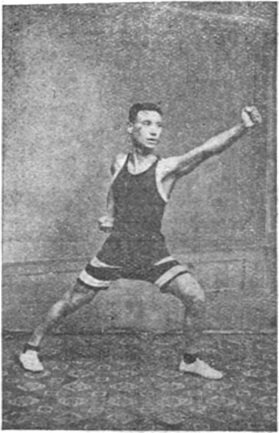

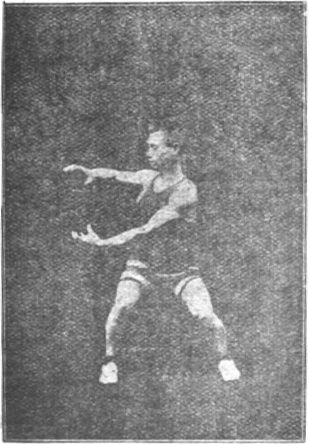

七、是時身體左轉。腹部內收。左腳收囘半步。與右腿倂齊。成左虛式。同時右臂內轉。眼平視。如第七圖。

7. Then your body turns to the left, your belly drawing back, as your left foot withdraws a half step [your right pivoting inward] for the thigh to pull in next to your right thigh, making a left empty stance, and your right arm at the same time arcs inward. Your gaze is level. See photo 1.7:

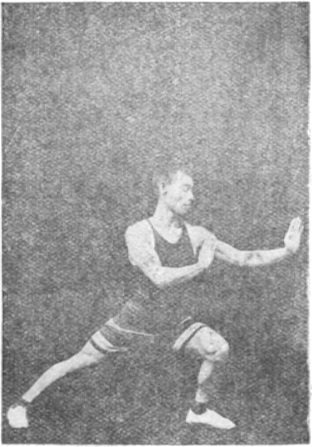

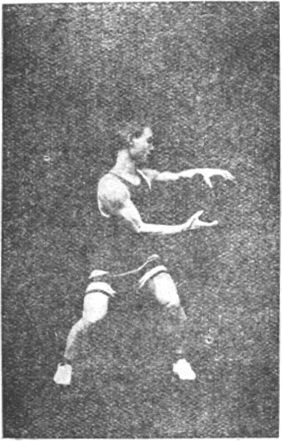

八、左腳向右腳後方。退後一大步。右腳下彎。左腳伸直。成右弓式。同時左掌下掛。復上挑。右掌上衝。復下劈。兩臂成弧形。眼視右掌。如第八圖。

8. Then your left foot retreats a large step behind your right foot, your right leg bending, your left leg straightening, making a right bow stance. At the same time, your left palm hangs down and then carries upward as your right palm thrusts up and then chops down, your arms making a curved shape. Your gaze is toward your right palm. See photo 1.8:

停立正。成抱肘式。

Then finish by standing at attention [withdrawing your right foot] and making the wrapped-elbows position.

右式預備圖

Preparation posture on the right side:

立正抱肘式。眼平視。胸挺起。腰直。腿倂。兩腳約距離六十度。兩拳置於腰間。兩肘向後。如上圖。

Stand at attention with your elbows wrapped back, your gaze level. Your chest is sticking out, your torso upright. Your legs are together, your feet spread to make a sixty degree angle. Your fists are placed at your waist, your elbows pointing behind. See photo 1.9a:

一、右拳變掌。由腰間向上經額前往右肩前下按至左腋。眼平視。如第一圖。

1. Your right fist becomes a palm, rises from your waist, passes in front of your forehead, goes in front of your right [left] shoulder, and pushes down until in front of your left armpit. Your gaze is level. See photo 1.9b:

二、是時左拳卽變掌。由左腋下經右掌上穿出。向左伸直。手指向上。五指倂齊。掌邊向左。右掌貼左肩。掌心向內。掌形似柳葉。名曰柳葉掌。眼視左掌。身體順勢稍左轉。同時卽伸右腿。左膝曲為九十度。全身重量坐於右腿上。如第二圖。

2. Then your left fist becomes a palm and goes from your left armpit, threading out over your right palm, and extending to the left, the fingers pointing upward, fingers together, the palm edge facing to the left, your right palm near your left shoulder with the center of the hand facing inward. Each palm is making a shape like a willow leaf, and thus it is called a “willow leaf” palm. Your gaze is toward your left palm. Your torso goes along with the movement by turning slightly to the left and your right leg extends [to the right], your left knee bending to make a ninety degree angle, the weight sitting onto your right [left] leg. See photo 1.10:

三、右掌由左肩向右伸直。指端向下。掌背近腿。身稍右轉。眼視右掌。如第三圖。

3. Your right palm goes from your left shoulder and extends to the right, the fingers pointing downward, the back of the palm near your [right] leg, as your torso slightly turns to the right. Your gaze is toward your right palm. See photo 1.11:

四、是時右掌沿腿上挑。卽彎右腿。伸左腿。右腰亦卽同時伸縮。身體順勢稍右轉。右掌尖與鼻齊。左掌尖與頭頂齊。兩肘內扣。眼視右掌。兩臂形似扁擔。名曰扁擔式柳葉掌。如第四圖。

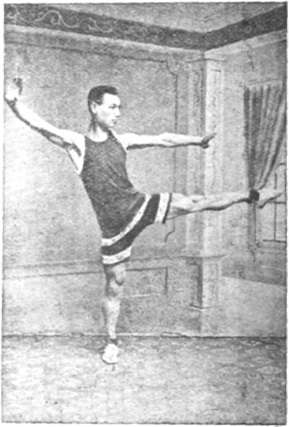

4. Your right palm passes along your [right] leg and carries upward as your right leg bends and your left leg straightens, the right side of your waist stretching, and your torso goes along with the movement by turning slightly to the right. Your right fingertips are at nose level, your left fingertips at headtop level, and your elbows are covering inward. Your gaze is toward your right palm. Your arms look as though they are carrying a shoulder pole, and thus this posture is described as “carrying a pole with willow-leaf palms”. See photo 1.12:

五、右掌上衝。左掌下掛。同時左腿隨左臂前上一步。身體順左腿猛閃向前。左腳趾點地成丁式。眼平視。如第五圖。

5. Your right palm thrusts upward as your left palm hangs downward. At the same time, your left leg goes along with your left arm by stepping forward, your body correspondingly going suddenly forward, your left toes touching the ground, making a T-shaped stance. Your gaze is level. See photo 1.13:

六、同時身體由右後轉。是時右腳再向前一大步。左腿下彎。右腳伸直。同時右掌後劈。左掌前挑。眼視右掌。如第六圖。

6. Then your torso turns to the right rear as your right [left] foot takes a large step forward, the leg bending, your right leg straightening. At the same time, your right palm chops to the rear, your left palm carrying in front. Your gaze is toward your right palm. See photo 1.14:

七、是時身體右轉。腹部內收。右腳收囘半步。與左腿倂齊。成右虛式。同時左臂內轉。眼平視。如第七圖。

7. Then your body turns to the right, your belly drawing back, as your right foot withdraws a half step [your left pivoting inward] for the thigh to pull in next to your left thigh, making a right empty stance, and your left arm at the same time arcs inward. Your gaze is level. See photo 1.15:

八、右腳向左腳後方退後一大步。左腳下彎。右腳伸直。成左弓式。同時右掌下掛。後上挑。左掌上衝。復下劈。兩臂成弧形。眼視左掌。如第八圖。

8. Then your right foot retreats a large step behind your left foot, your left leg bending, your right leg straightening, making a left bow stance. At the same time, your right palm hangs down and then carries upward as your left palm thrusts up and then chops down, your arms making a curved shape. Your gaze is toward your left palm. See photo 1.16 [again followed by withdrawing into standing at attention and making the wrapped-elbows position]:

生理上之關係

Physiological aspect:

閃轉用掌。循行進退。此為四肢之動作。又為腰部之運動。蓋此節縮小柔軟。活動四肢。流通氣血。舒展筋骨。為開始運動之準備。亦為講究生理之主要部分。並將各主要肌肉功用分析如左。

To suddenly turn around wielding palms while advancing and retreating is an exercise for the four limbs which also works the waist area. This exercise reduces excessive softness, livens the limbs, circulates energy and blood and stretches the sinews and bones. To get ready for the exercise, attention should be given to the major parts of the body that are involved in it. Listed below are the main muscles that are being worked:

一、以下各肌肉之名詞。悉據科學名詞審查會所定者。閃轉用掌。卽兩臂左右展開。及臂向內轉與向外轉等動作。

(Used below are names for specific muscles based on the verified proper scientific terminology.) 1. Suddenly turning around wielding palms involves the arms spreading to the left and right, as well as the arms making arcs inward and outward.

甲、兩臂左右展開。主要肌肉。

A. Spreading the arms to the left and right works these muscles:

岡上 三角 斜方三分之一等肌肉

supraspinatus, deltoids, lower trapezius.

乙、臂向內轉。主要肌肉。

B. Arcing the arm inward works these muscles:

背闊 大圓 胸大 三角 肩胛下等肌肉

latissimus dorsi, teres major, pectoralis major, deltoids, subscapularis.

丙、臂向外轉。主要肌肉。

C. Arcing the arm outward works these muscles:

岡下 三角 小圓等肌肉

infraspinatus, deltoids, teres minor.

二、循行進退。卽大腿內轉與外轉。並屈小腿與伸小腿等動作。

2. Advancing and retreating involves rotating the upper leg inward and outward, as well as bending and straightening the lower leg.

甲、大腿內轉。主要肌肉。

A. Turning the upper leg inward works these muscles:

闊筋模張 臀小 臀中 腰大等肌肉

tensor fasciae latae, gluteus minimus, gluteus medius, psoas major.

乙、大腿外轉。主要肌肉。

B. Turning the upper leg outward works these muscles:

外閉孔 臂大 縫匠 恥骨等肌肉

external obturator muscle, gluteus maximus, sartorius, pectineus.

丙、屈小腿。主要肌肉。

C. Bending the lower leg works these muscles:

縫匠 股薄 半腱 半模 股二頭 腓腸淺 蹠膕等肌肉

sartorius, gracilis, semitendinosus, semimembranosus, biceps femoris, gastrocnemius, popliteus.

丁、伸小腿。主要肌肉。

D. Extending the lower leg works these muscles:

股四頭 股直 股內側 股外側 股中間等肌肉

Quadriceps (rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, vastus intermedius).

心理上之關係

Psychological aspect:

此節動作。行如撥草之蛇。轉如閃電之急。一舉一動。儼有勁敵在前。得心應手之妙。

In this exercise, the stepping is like a snake slithering through the grass and the turning is like a flash of lightning. With every movement, imagine there is a formidable opponent in front of you, and then you will perform it skillfully.

教育上之關係

Pedagogical aspect:

此節專練習手眼身法步。運用神經之連合。發揮奮鬭之本能。養成耐勞自信判斷敏捷勇敢自主有恆諸德性。此為武術之技能。而深合教育上之訓練。

This exercise focuses on training methods of hand, eye, body, and step. It trains coordination of the nervous system and thus develops one’s fighting instincts. It cultivates the virtuous qualities of hard work, self-confidence, judgment, quick wits, courage, initiative, and perseverance. These skills in martial arts strongly conform to skills needed in teaching.

–

第二節 改正運動(兼有軀幹之動作)

Section 2: AN EXERCISE OF REALIGNING (which also works the torso)

種類

Type of exercise:

俯仰伸縮。上呼下吸。

Lean forward and back, extending and retracting, exhaling when the hands are above, inhaling when the hands are below.

術名

Name of the technique:

十字佩虹鴛鴦手。

CROSSED HANDS SPREADING A RAINBOW, MANDARIN DUCK HANDS

實用要訣

Keys to the exercise:

來無形。去無蹤。(卽鈎摟挂打巧妙之形容詞也)按此六字巧妙之法。不在文字上空求。在學者熟練精通。當得此中三昧。

“Enter invisibly and then exit without a trace.” (This describes the actions of hooking and dragging, carrying and striking.) These words refer to a level of skillfulness and are not some just airy poetry. Once you have mastered these movements, you will awaken to the meaning.

實習動作

Practice method:

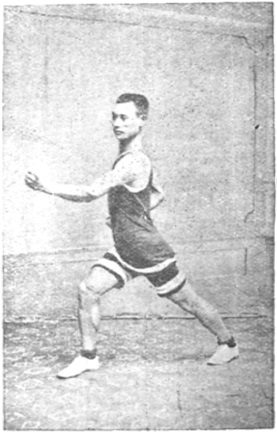

預備

Preparation posture:

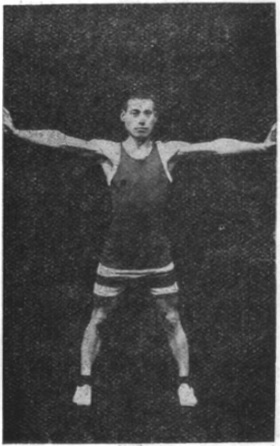

開立抱肘。兩腳距離等於兩肩闊。眼前視。腰直。挺胸。

From standing at attention with your elbows wrapped back, your feet spread apart to shoulder width. Your gaze is forward, your torso is upright, and your chest is sticking out.

一、上體半面向左轉。兩腿下彎成騎馬式。同時兩拳變掌。交叉成十字形。上體稍向右轉。兩掌至膝前。卽變鈎向左右摟開。而膝前須前後相對。眼視前。挺胸。直腰。兩鈎與肩成垂直線。兩手交叉成十字形。名曰十字手。如第一第二圖。

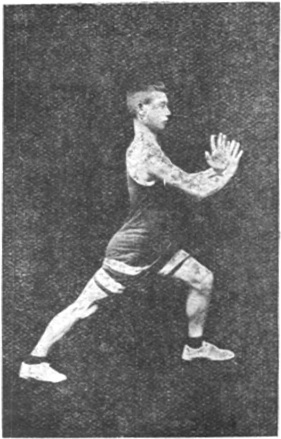

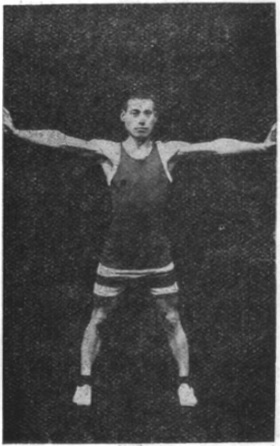

1. Your upper body turns halfway to the left and your legs bend to make a horse-riding stance [left empty stance] as your fists become palms and cross to make an X shape in front of your knees, your upper body turning to the right [left]. Then your palms become hooks and drag apart to the sides to be in line with your knees. Your gaze is forward. Your chest is sticking out and your torso is upright. Your arms from shoulders to hands are hanging down and making vertical lines. Because of your palms crossing, this technique is called CROSSED HANDS. See photos 2.1 and 2.2:

二、兩鈎變掌。交叉成十字形。兩肘近肋。上體卽向後仰。右腳稍伸。左腳稍彎。同時兩掌向左右分開。肘仍貼於肋。掌心向前。手指稍曲分開。形似荷葉。名曰荷葉掌。兩掌位於兩肩之前。腹部收緊。胸挺起。眼前視。名曰十字佩虹式。如第三第四圖。

2. Your hooks become palms and cross to make an X shape, your elbows staying near your ribs, your upper body leaning back, your right [left] leg slightly straightening, left leg [right] slightly bending. Then your palms spread apart to the sides, your elbows still staying near your ribs, the centers of the hands facing forward, fingers slightly bent and spread apart. The shape is like lotus leaves, and so they are called “lotus leaf” palms. Your palms are positioned in front of your shoulders. Your belly is drawn back and your chest is sticking out. Your gaze is forward. This technique is called CROSSED HANDS SPREADING A RAINBOW. See photos 2.3 and 2.4:

三、鬆肩。兩掌向前直撲。同時左腿伸直。成右弓左箭步。或馬式亦可。惟兩臂平行。指尖與肩尖成半弧形。手指向上分開。用掌底使勁。形似嬰兒撲乳。名曰嬰兒撲乳式。

3. Your shoulders loosen and your palms pounce forward as your left [foot steps out and your right] leg straightens, making a stance of right [left] leg a bow, left [right] leg an arrow, though it can also done in a horse-riding stance. Your arms are level and form semicircles from shoulder to fingertips, the fingers pointing upward and spread apart, power expressing at the heels of the palms. This technique looks like an infant reaching out to be breast-fed, and so it is called INFANT GRABS AT ITS MOTHER’S BREASTS. See photo 2.5:

循環連續六次。再換左向後轉。練左式。如第五圖。

Perform this series of movements six times, then turn around to the left [right] and practice it on the other side.

四、兩掌交叉成十字形。上體向前俯。兩掌至膝前。卽變鈎向左右摟開。同時左膝仍曲成騎馬式。眼前視。挺胸。直腰。兩手交叉成十字名曰十字手。與第一二圖同。圖從略。

4. [Your feet pivot to the left (right) to point their toes behind you,] your legs bending to again make a horse-riding stance [right empty stance] as your palms cross to make an X shape in front of your knees, your upper body leaning forward [while turning around to the right], Then your palms become hooks and drag apart to the sides. Your gaze is forward. Your chest is sticking out and your torso is upright. Because of your palms crossing, this technique is called CROSSED HANDS. This is the same technique as in photos 2.1 and 2.2. See photos 2.6 and 2.7:

五、兩足尖向左後轉。左膝稍曲。右膝彎。同時兩鈎變掌。交叉成十字形。兩肘貼肋。上體向後仰。交叉。兩掌卽向左右分開。肘仍貼於肋。掌心向前。五指稍曲。分開。形似荷葉。名曰荷葉掌。兩掌位於兩肩之前。腹部收緊。胸挺起。眼前視。名曰十字佩虹式。如第六第七圖。

Your hooks become palms and cross to make an X shape, your elbows staying near your ribs, your upper body leaning back. Then your palms spread apart to the sides, your elbows still staying near your ribs, the centers of the hands facing forward, fingers slightly bent and spread apart. The shape is like lotus leaves, and so they are called “lotus leaf” palms. Your palms are positioned in front of your shoulders. Your belly is drawn back and your chest is sticking out. Your gaze is forward. This technique is called CROSSED HANDS SPREADING A RAINBOW. See photos 2.6 and 2.7 [2.8 and 2.9]:

六、鬆肩。兩掌向前直撲。同時右腿伸直左弓右箭步。或馬式亦可。兩臂平行。指尖與肩尖成半弧形。手指向上分開。五指用掌底使勁。形似嬰兒撲乳。名曰嬰兒撲乳式。如第八圖。

6. Your shoulders loosen and your palms pounce forward as your right [foot steps out and your left] leg straightens, making a stance of left [right] leg a bow, right [left] leg an arrow, though it can also done in a horse-riding stance. Your arms are level and form semicircles from shoulder to fingertips, the fingers pointing upward and spread apart, power expressing at the heels of the palms. This technique looks like an infant reaching out to be breast-fed, and so it is called INFANT GRABS AT ITS MOTHER’S BREASTS. See photo 2.8 [2.10]:

再演十字手。如第九第十圖。

Then perform CROSSED HANDS again, the same as in photos 9 and 10 [6 and 7].

如是循環連續演習六次。再向右後轉。演習六次。又向左。卽名曰左右連環式。

Perform this series of movements six times, then turn around and practice it on the other side another six times. This whole exercise is called CONTINUOUS MOVEMENT ON BOTH SIDES.

生理上之關係

Physiological aspect:

上呼下吸者。所以擴張胸廓。增進肺量。使橫膈膜充分運動。前俯後仰者。所以伸縮腹壁筋。以助長消化力。且兼有改正動作。使胸襟舒暢。脊柱無偏倚之弊。並將各主要肌肉功用分析如左。

Exhale when your hands are above. Inhale when your hands are below. This expands your rib cage, increasing lung capacity, and exercising your diaphragm. Leaning forward and back causes your abdominal wall to stretch and contract, encouraging digestion. This also serves as a corrective moment, the expanding of your chest discouraging your spine from curving into improper angles. Listed below are the main muscles that are being worked:

一、下俯上仰。卽脊梁前彎。與伸脊梁之動作。

1. Leaning forward and back involves the spine curving and straightening.

甲、脊梁前彎。主要肌肉。

A. The spine bending forward works these muscles:

項最長 頭最長 前斜角 腰直 腸內斜 腹外斜 腹橫等肌肉

longissimus cervicis, longissimus capitis, scalenus anterior, dorsal erector muscle, internal oblique muscle, external oblique muscle, transverse abdominis.

乙、伸脊梁。主要肌肉。

B. The spine straightening works these muscles:

下後鋸 頭夾 項半棘 背半棘 斜方等肌肉

serratus posterior inferior, splenius capitis, semispinalis cervicis, semispinalis thoracis, trapezius.

二、轉體向左右。卽轉脊梁之動作。

2. Your body turning to the left and right involves rotation in the spine.

甲、轉脊梁。主要肌肉。

A. Rotation in the spine works these muscles:

腹內斜 腹外斜 項半棘 背半棘等肌肉

internal oblique muscle, external oblique muscle, semispinalis cervicis, semispinalis thoracis.

心理上之關係

Psychological aspect:

此節動作。形態甚為美觀。並簡而易學。無論少長咸宜。練熟後。手法身法步法。自有生龍活虎之態。如此人安得不樂於學習乎。

This exercise looks very artistic, and yet it is also simple and easy to learn, as well as suitable for young and old alike. Once you have practiced it to a level of skillfulness, these actions of your hands, body, and feet will be full of vitality. This being the case, how could anyone not enjoy learning it?

教育上之關係

Pedagogical aspect:

此節運動。非但鍛練體魄。活潑精神。而且有衞身抗敵之術。可為個人團體之保障。此頗合於現代教育上之需要。

This exercise not only toughens the body and livens the spirit, it is also useful for defending oneself against opponents. Since it can help ensure the safety of individuals within the group, it thus strongly aligns with the requirements of what should be taught in the modern age.

–

第三節 上肢運動

Section 3: AN EXERCISE FOR THE UPPER BODY

種類

Type of exercise:

原地運用掌肘指腕之伸縮。

Standing in place, you work the flexibility of your palms, elbows, fingers, and wrists.

術名

Name of the technique:

五花礮

EXPLOSIVE FLOURISHES

實用要訣

Keys to the exercise:

此節有伸捰刁拏鎖扣勾掛擒打。分合連環。各動作。各盡其手法之妙用。為應敵還敵之巧具。其出奇制勝之能。洵為武術之要訣也。

This exercise contains the elements of reaching out to catch, drawing in to seize, locking up, hanging aside, and capturing to strike. The movements are a continuous extending and withdrawing, and are entirely a matter of using subtle hand techniques to skillfully defend against and counterattack an opponent. The ability to defeat your opponent by using unexpected maneuvers is a hallmark of martial arts.

實習動作

Practice method:

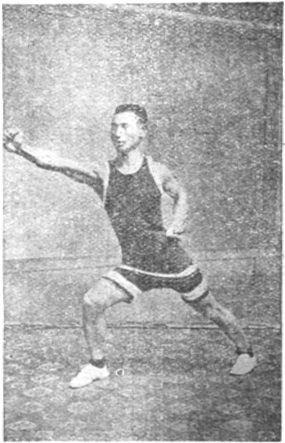

預備

Preparation posture:

由立正抱肘。兩腳離開。與兩肩成垂直線。兩腿下彎。為四十五度。成半馬式。

From standing at attention, elbows wrapped back, your feet spread apart to shoulder width and your legs bend forty-five degrees to make a half horse-riding stance.

一、右拳變掌。向前斜下伸。指端向前。掌緣切地。掌底對小腹。距離約七寸許。臂膊伸直。肘內扣。腰直。胸挺。眼前視。出掌如切物。名曰切掌。如第一圖。

1. Your right fist becomes a palm and extends forward and diagonally downward, the fingertips pointing forward, the edge of the palm slicing toward the ground, the heel of the palm in line with and about three quarters of a foot away from your lower abdomen, with the arm straightening but the elbow covering inward. Your torso is upright, your chest sticking out, your gaze forward. The palm goes out as though it is slicing through an object, and thus it is called a “slicing palm”. See photo 3.1:

二、右掌上掛。同時大膊貼肋。屈肘內扣。手掌上掛。翻手腕向後。手心向前。掌卽右刁。虎口向上。手背近肩。約四寸許。先掛後刁。名曰掛掌。如第二圖。

2. Your right palm carries upward, the upper arm staying near your ribs, the elbow bending and covering inward. As the palm goes upward, the wrist turns outward so the center of the hand is facing forward. The palm then hooks to the right, the tiger’s mouth facing upward, the back of the hand a few inches away from the shoulder. First carry, then hook. This technique is called a “hanging palm”. See photo 3.2:

三、右掌斜向前伸。運掌底擊敵。右肩順手勢鬆開。腰稍轉向左。指端對鼻尖。手肘內扣。掌似荷葉。名曰荷葉掌。如第三圖。

3. Your right hand extends diagonally forward, sending the heel of the palm to strike an opponent. Your right shoulder loosens and extends along with the movement of the hand, and your torso slightly turns to the left. The fingertips are at nose level, the elbow covering inward. The palm is making a lotus-leaf shape, and thus is called a “lotus-leaf palm”. See photo 3.3:

四、右臂由前下斫。至大腿後方。同時掌卽變鈎。摟至臀後。手肘稍曲。上挑下摟。均須迅速活潑。而有精神。眼前平視。胸挺。腰直。以上四動。均半馬式。左拳仍抱肘。式如第四圖。

4. Your right arm then chops downward and goes past your [right] thigh, the palm becoming a hook, after which it will drag back until behind the buttock, the elbow slightly bent. The actions of carrying upward and then dragging downward have to be quick, lively, and spirited. Your gaze is forward and level. Your chest is sticking out and your torso is upright. These four movements are all performed in a half horse-riding stance. Your left fist remains in a wrapped-elbow position. See photo 3.4:

五、左拳變掌。向前斜下伸。指端向前。掌緣切地。掌底對小腹。距離約七寸許。臂膊伸直。肘內扣。腰直。胸挺。眼前視。出掌如切物。名曰切掌。如第五圖。

5. [Your right hand returns to your waist, then] your left fist becomes a palm and extends forward and diagonally downward, the fingertips pointing forward, the edge of the palm slicing toward the ground, the heel of the palm in line with and about three quarters of a foot away from your lower abdomen, with the arm straightening but the elbow covering inward. Your torso is upright, your chest sticking out, your gaze forward. The palm goes out as though it is slicing through an object, and thus it is called a “slicing palm”. See photo 3.5:

六、左掌上挑。同時大膊貼肋。屈肘內扣。手掌上掛。翻手腕向後。手心向前。掌卽左刁。虎口向上。手背近肩。約四寸許。先掛後刁。名曰掛掌。如第六圖。

6. Your left palm carries upward, the upper arm staying near your ribs, the elbow bending and covering inward. As the palm goes upward, the wrist turns outward so the center of the hand is facing forward. The palm then hooks to the left, the tiger’s mouth facing upward, the back of the hand a few inches away from the shoulder. First carry, then hook. This technique is called a “hanging palm”. See photo 3.6:

七、左掌斜向前伸。運掌底擊敵。左肩順手勢鬆開。腰稍轉向右。指對鼻尖。手肘內扣。掌似荷棄。名曰荷葉掌。如第七圖。

7. Your left hand extends diagonally forward, sending the heel of the palm to strike an opponent. Your left shoulder loosens and extends along with the movement of the hand, and your torso slightly turns to the right. The fingertips are at nose level, the elbow covering inward. The palm is making a lotus-leaf shape, and thus is called a “lotus-leaf palm”. See photo 3.7:

八、左臂由前下斫。至大腿後方。同時掌卽變鈎。摟至臀後。手腕稍曲。上挑下摟。均須迅速活潑。而有精神。眼前平視。胸挺腰直。以上四動。均半馬式。右手仍鈎於臀後。如第八圖。

8. Your left arm then chops downward and goes past your [left] thigh, the palm becoming a hook, after which it will drag back until behind the buttock, the elbow slightly bent. The actions of carrying upward and then dragging downward have to be quick, lively, and spirited. Your gaze is forward and level. Your chest is sticking out and your torso is upright. These four movements are all performed in a half horse-riding stance. Your right hand remains as a hook behind you [remains in a wrapped-elbow position according to the photos]. See photo 3.8:

生理上之關係

Physiological aspect:

此節練習兩臂大小諸肌與腱。各盡其伸縮翻轉之能。實為運動上肢之良好動作也。此項動作之複雜。按運動生理上之次序。『應列在運動次序三分之一』故列於第三節。當為腦系部間接之運動。誠為生理衞生必要之動作也。並將各主要肌肉功用分析如左。

This exercise trains the major and minor arm muscles. Its actions of extending, withdrawing, and arcing are indeed excellent movements for working the upper arm. This rather complex series of movements is in accordance with the method of arranging exercises for the best physiological effects: “A third of the exercises should be complex.” Therefore this exercise is placed third out of the first three. Due to its complexity, it is indirectly an exercise for the brain. It is also an indispensable exercise for promoting health. Listed below are the main muscles that are being worked:

掌肘指腕之伸縮卽髆骨向前。髆骨向下。髆骨向後。屈小臂與伸小臂。及掌向外。各動作。

These actions of extending and withdrawing the palm, elbow, fingers, and wrist involve a variety of movements including the shoulder blade moving forward, downward, and back, the forearm bending and extending, and the palm going outward.

甲、髆骨向前。主要肌肉。

A. The shoulder blade going forward works these muscles:

前鋸 胸大 胸小等肌肉

serratus anterior, pectoralis major, pectoralis minor.

乙、髆骨向下。主要肌肉。

B. The shoulder blade going downward works these muscles:

斜方 胸小 背闊 胸大等肌肉

trapezius, pectoralis minor, latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major.

丙、髆骨向後。主要肌肉。

C. The shoulder blade going back works these muscles:

腰方 背闊 大菱等肌肉

quadratus lumborum, latissimus dorsi, rhomboid major.

丁、屈小臂。主要肌肉。

D. Bending the forearm works these muscles:

肱雙頭 肱前 旋前圓 手與指之伸 手之伸等肌肉

biceps brachii, brachialis, pronator teres, hand & finger extensors.

戊、伸小臂。主要肌肉。

E. Extending the forearm works these muscles:

肱三頭 肱前 手與指之伸等肌肉

triceps brachii, brachialis, hand & finger extensors.

己、掌內外。主要肌肉。

F. The palm going outward works these muscles:

掌長 撓側伸腕短 尺側伸腕等肌肉

palmaris longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor carpi ulnaris.

心理上之關係

Psychological aspect:

此節動作。練習眼明手快之技能。凡動作之遲速。以思索力之敏鈍為轉移。練習此種運動。當有比較之姓質。而生競爭之心。則收心理上之功用大矣。

This exercise trains guickness of eyes and hands. Whatever the speed of your movement, focus on switching nimbly from one movement to another. Practicing this kind of exercise will help to build a more ambitious nature and develop a more competitive mindset, and therefore it is a very useful psychological tool.

教育上之關係

Pedagogical aspect:

此節運動。練習心靈手敏。以之為學。必日進於高明之域。以之接物。有隨機應變之方。對於智育關係綦重。

This exercise trains agility of both mind and hand. To become educated, you have to constantly increase your range of qualifications, because to deal with the world, you have to have the means to adapt to situations. Such an exercise is thus extremely helpful for one’s intellectual development.

–

第四節 腰胯運動(兼全身之動作)

Section 4: AN EXERCISE FOR THE WAIST & HIPS (as well as the whole body)

種類

Type of exercise:

原地彈機活步。左右閃轉踹踢。

This is a method of staying where you are and performing a “snapping step”, as well as suddenly turning to the side and sending out a kick.

術名

Name of the technique:

雙稱十字腿。

CROSS-SHAPED KICK

實用要訣

Keys to the exercise:

武術致勝。多在進退。且進退之要。必須腰腿一致。以拳腳之動作為轉移。所行之動作貴速。以不誤拳腳致勝之機為合法。此節拳腳。務須全體一致。其發拳腳須有抨簧之靈。始收致勝之効也。

Victory through martial arts often comes down to advancing and retreating. To advance and retreat effectively, your waist and hips have to function as a single unit. The movements of your fists and feet should be quick but should not be mis-timed. For this exercise, your hands and feet have to work together. Your punches and kicks must shoot out with the nimbleness of mechanical springs, and then you will be able to achieve victory.

實習動作

Practice method:

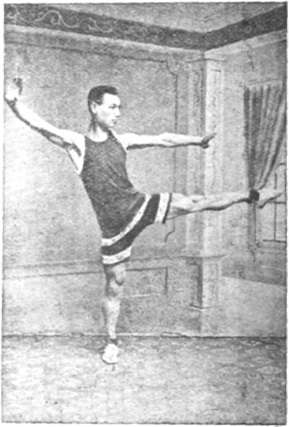

預備

Preparation posture:

立正抱肘。式面向南。

Stand at attention, elbows wrapped back, facing toward the south.

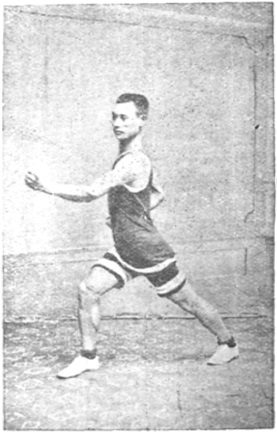

一、左腳向東北出一步。同時兩拳變掌。由西南上角成陰陽和合掌。猛向東北拏扎。左手拏至腰間。仍抱肘式。右掌變拳。西南上角往下打。手心向上。右大膊貼於肋。成左弓式。面向東。此種動作。名曰前拏手。與後扎手。如第一圖。

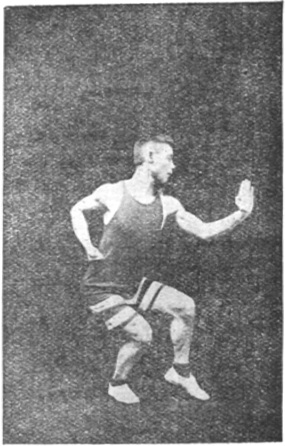

1. Your left foot takes a step out to the northeast as your fists become palms, which come together as prayer palms pointing toward the southwest and then fiercely jabbing toward the northeast. Then your left hand [again becoming a fist] pulls back to your waist, returning to the wrapped-elbow position, as your right palm becomes a fist and strikes toward the southwest, the center of the hand facing upward, the upper arm staying near your ribs. You are in a left bow stance, your torso facing toward the east. This technique is called GRABBING & JABBING. See photo 4.1:

二、左拳由腰間直向東北上角衝出。與鼻平。同時右扎。拳收囘。置於腰間。仍抱肘式。此動作名曰應面拳。如第二圖。

2. Your left fist thrusts upward to the northeast until at nose level, your right fist at the same time withdrawing to be placed at your waist, again making a wrapped-elbow position. This movement is called “punch to the face”. See photo 4.2:

三、右拳向東斜下衝出。與心房齊。同時左拳上挑。面向東。腰直。胸挺。眼前視。此動作名曰黑虎搗心式。如第三圖。

3. Your right fist thrusts out diagonally toward the east to be at solar plexus level as your left fist carries upward. You are facing toward the east. Your torso is upright and your chest is sticking out. Your gaze is forward. This technique is called BLACK TIGER GOES FOR THE HEART. See photo 4.3:

四、雙拳變掌。左掌向上。與右掌交叉。在頂前。手心向外。同時轉體向左閃。眼前視。挺胸。直腰。此動作名曰過頂式。如第四圖。

4. Your fists become palms and cross in front of your headtop [chest according to the photo], left palm on top, the palms facing outward, as your torso turns to the left. Your gaze is forward. Your chest is sticking out and your torso is upright. This technique is called PASSING OVER THE HEADTOP. See photo 4.4:

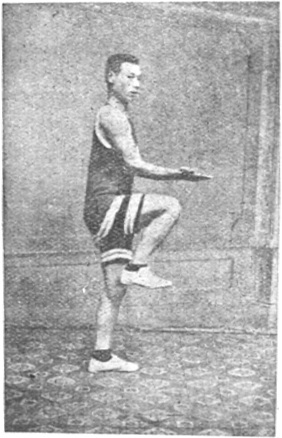

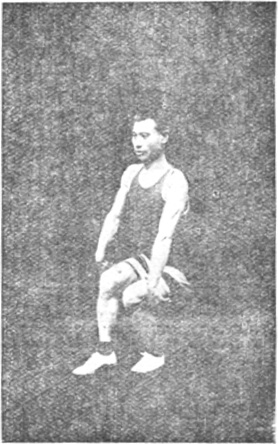

五、兩掌左右下落。合於懷前相切。卽提起右腿。腰直。胸挺。眼平視。此動作名曰懷中抱月式。如第五圖。

5. Your palms lower to the sides and then come together in front of your chest as your right leg lifts. Your torso is upright and your chest is sticking out. Your gaze is level. This technique is called EMBRACING THE MOON. See photo 4.5:

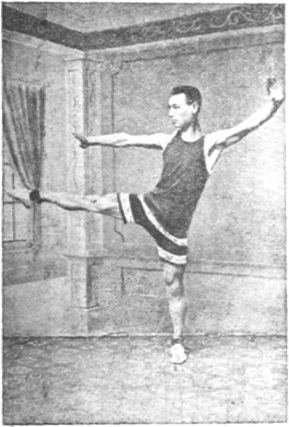

六、雙掌向東西撐開。左掌與頭頂平。右掌與肩平。同時右腿向東排出。腿伸直。成九十度直角。全身向左閃。眼視東。名曰雙稱腿。如第六圖。

6. Your palms brace away toward the east and west, your left palm at headtop level, your right palm at shoulder level, as your right leg kicks out to the east, your legs straightening and making a ninety degree angle, your torso turning to the left. Your gaze is toward the east. This technique is called KICK WITH BOTH PALMS BRACING. See photo 4.6 [missing from the book, but we can fill the gap by reversing photo 4.12]:

七、承上右腿排出。右腳尚未落地時。左腿彈起向後退。右腳卽落於左腳所立之部位。此謂為彈機活步。同時右掌卽向東南拏至腰間。成抱肘式。左掌卽握拳向東下扎。左膊貼肋。手心向上。如第七圖。

7. Continuing from your right leg kicking out, before your right foot has fully come down, your left foot suddenly retreats, and then your right foot comes down next to your left foot. This action is called a “snapping step”. At the same time, your right hand [again becoming a fist] pulls back toward the southeast to make the wrapped-elbow position at your waist, and then your left palm grasps into a fist and strikes toward the east, the upper arm staying near your ribs, the center of the hand facing upward. See photo 4.7:

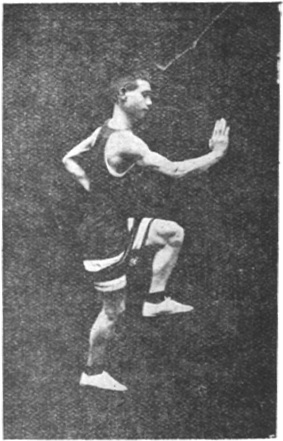

八、右拳由腰間直向東北上角衝出。與鼻平。同時左扎。拳收囘置於腰間。仍抱肘式。此動作名曰應面拳。如第八圖。

8. Your right fist thrusts upward to the northeast until at nose level, your left fist at the same time withdrawing to be placed at your waist, again making a wrapped-elbow position. This movement is called “punch to the face”. See photo 4.8:

九、左拳向東斜下衝出。與心房齊。同時右拳上挑。面向東。腰直。胸挺。眼視前。此動作名曰黑虎搗心式。如第九圖。

9. Your left fist thrusts out diagonally toward the east to be at solar plexus level as your right fist carries upward. You are facing to the east. Your torso is upright and your chest is sticking out. Your gaze is forward. This technique is called BLACK TIGER GOES FOR THE HEART. See photo 4.9:

十、雙拳變掌。右掌向上。與左掌交叉在頂前。手心向外。同時轉體向右閃。眼視前。挺胸。直腰。此動作名曰過頂式。如第十圖。

10. Your fists become palms and cross in front of your headtop [chest according to the photo], right palm on top, the palms facing outward, as your torso turns to the right. Your gaze is forward. Your chest is sticking out and your torso is upright. This technique is called PASSING OVER THE HEADTOP. See photo 4.10:

十一、兩掌左右下落。合於懷前相切。卽提起右腿。腰直。挺胸。眼平視。此動作名曰懷中抱月式。如第十一圖。

11. Your palms lower to the sides and then come together in front of your chest as your right [left] leg lifts. Your torso is upright and your chest is sticking out. Your gaze is level. This technique is called EMBRACING THE MOON. See photo 4.11:

十二、雙掌向東西撐開。右掌與頭頂平。左掌與肩平。同時左腿向東排出。腿伸直。成九十度直角。向右閃。眼視東。名曰雙稱腿。如第十二圖。

12. Your palms brace away toward the east and west, your right palm at headtop level, your left palm at shoulder level, as your left leg kicks out to the east, your legs straightening and making a ninety degree angle, your torso turning to the right. Your gaze is toward the east. This technique is called KICK WITH BOTH PALMS BRACING. See photo 4.12:

生理上之關係

Physiological aspect:

此節為彈機活步之動作。能振動內臟。激刺腸胃。且能助增消化力。促進血液循環。使各關節之腱增强彈力性。並將各主要肌肉之功用。分析如左。

This exercise involves a “snapping step”, which gives a shake to the internal organs, particularly stimulating the stomach and intestines, thereby aiding digestion. It also promotes better blood circulation and enhances the elasticity of the tendons in the joints. Listed below are the main muscles that are being worked:

一、前後手拏扎。卽兩臂下垂與屈伸小臂之動作。

1. The hands pulling back and jabbing forward involves the arms being pulled down, as well as the forearm bending and extending.

甲、兩臂下垂。主要肌肉。

A. Pulling the arms down works these muscles:

背闊 大圓 斜方下三分之一 胸大等肌肉

latissimus dorsi, teres major, lower trapezius, pectoralis major.

乙、屈小臂。主要肌肉。

B. Bending the forearm works these muscles:

肱二頭 肱前 肱前 前旋圓等肌肉

biceps brachii, brachialis, pronator teres.

兩臂上伸下伸。卽伸小臂。丙、伸小臂。主要肌肉。

C. Extending the forearm works these muscles:

肱三頭 胸大 橈側伸腕短 尺側伸腕等肌肉

triceps brachii, pectoralis major, extensor carpi ulnaris.

提腿舉腿側排。卽大腿前舉。及左右展開之動作。二、左右閃轉踹踢。卽大腿前舉。及左右展開之動作。

2. Suddenly turning and kicking to the side involves the upper leg raising in front and then the leg extending to the side.

甲、大腿前舉。及左右展開。主要肌肉。

A. Raising the upper leg and extending to the side works these muscles:

梨狀 內閉 孖上孖下 縫匠 闊筋膜張等肌肉。

piriformis, internal obturator, superior gemellus, inferior gemellus, sartorius, tensor fasciae latae.

心理上與教育上之關係。

Psychological & pedagogical aspects:

俱見前節。

Same as in the previous exercise.

–

第五節 快速運動(兼有彈機跳躍之動作)

Section 5: AN EXERCISE FOR QUICKNESS (as well as explosiveness and jumping)

種類

Type of exercise:

彈機躍進快速之運動。

This is an exercise for developing ability for explosiveness and jumping.

術名

Name of the technique:

百步花。

TRAMPLING FLOWERS

實用祕法

Keys to the exercise:

要旨。練習身體輕捷。手腳靈便。為運用閃轉進步之妙法。及登高涉遠諸動作。有絕大之關係。常練能使手腳敏捷。進能取。退能守。行如飛。快如風。制勝於十步之外。此為武術之要法也。

The main idea is to train agility in the body and nimbleness in the hands and feet. It is an excellent exercise for improving dodging, turning, and advancing, and most of all for moving over large distances. Constant practice of it will make your hands and feet quick, so that you will be able to attack when you advance and defend when you retreat. Move as though flying, fast as wind. You should be able to rush in and subdue an opponent even when he is more than ten paces away. This is an important martial arts principle.

實習方法

Practice method:

預備動作

Preparation posture:

立正抱肘

Stand at attention, elbows wrapped back:

眼前視。挺胸。直腰。兩腳踵靠攏。腳尖分開。距離九十度。兩掌握拳。曲兩肘為九十度。兩拳置於腰間。肘尖向後。

Your gaze is forward, chest sticking out, your torso upright. Your heels are together, toes spread apart to make a ninety degree angle. Your hands grasp into fists and your arms bend into ninety degree angles as your fists are placed at your waist, elbows pointing behind you.

一、撩左掌。出左步。

1. Raise your left palm, stepping out with your left foot:

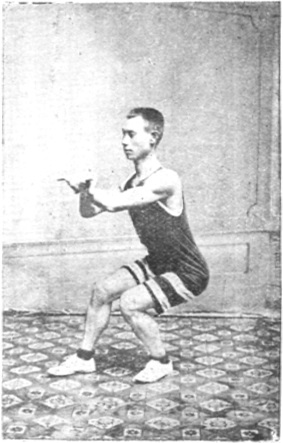

左拳變掌。伸直。由胯外向上撩。肘尖裏扣。成柳葉掌。同時左腳向前出一步。腳尖點地。腿曲成一百八十度四分之一。右拳仍抱肘。右腿稍曲。欲得姿勢準確。則掌尖與肩尖齊。成半弧形。鼻尖與肩尖對齊。肘與膝蓋腳尖對齊。前肘與後肘對齊。前膝與後膝對齊。名曰五齊。形似月斧。名曰闊斧式。如第一圖。

Your left fist becomes a palm and stands straight, raising upward from your [left] hip as a willow-leaf palm, the elbow covering inward. At the same time, your left foot steps forward, the toes touching down, the leg bent to a forty-five degree angle, your right fist remaining in a wrapped-elbow position, your right leg slightly bent. To get the posture to be precise, the fingertips of your palm should be at shoulder level, the arm making a half circle, and the shoulder should be pulled forward enough to be in line with your nose, the elbow should be in line with the knee and toes [of your front leg], your front elbow should be in line with your rear elbow, and your front knee should be in line with your rear knee. These are called the “five alignments”. The shape [of your front arm] is like a crescent-moon ax, or what is called a “broad ax”. See photo 5.1:

二、伸右腿。

2. Extend your right leg:

提右腿。曲膝。至九十度。向前伸。足尖斜向上。足踵用勁。向前排出。同時卽落地。名曰排腳式。如第二圖。

Your right leg lifts with the knee bent to make a ninety degree angle, then extends forward with the toes pointing diagonally upward, pushing out forward with power expressing at the heel, then immediately comes down. This technique is called a “crushing kick”. See photo 5.2:

三、右腳落於左腳前。卽提左腿。曲為九十度。腳尖向上。腳底稍向前。同時左掌由前向後。囘至腰間下擺。右拳變掌。伸直。由右胯外上撩。成柳葉掌。指尖對肩尖。肘尖裏扣。指尖至肩尖成半弧形。肘尖對腳尖。前膝對後膝。惟右腳落地時。用彈力。臨空搶步而進。卽向前搶一步。名曰右搶步腿。如第三圖。

3. Your right foot comes down in front of your left foot and then your left leg lifts forward, the knee bending to make a ninety degree angle, the toes lifted so that the sole of the foot is facing slightly forward. At the same time, your left palm swings downward and to the rear, withdrawing to your waist, while your right fist becomes a palm and stands straight, raising upward from your right hip as a willow-leaf palm, the fingertips at shoulder level, the elbow covering inward. The arm is making a half circle, the elbow is in line with your [left] toes, and your front knee is in a line with your rear knee [hip]. When your left foot comes down, it does so with a snapping energy, advancing as though walking on a tightrope, going forward with a “scraping step” [which is another way of describing the crushing kick]. This technique is called a “right scraping kick”. See photo 5.3:

四、左腳卽向前落地。卽提右腿向前曲膝。為九十度。足尖向上。腳底稍向前。同時右臂由前向後。囘至腰間。下擺。左掌上挑。成柳葉掌。指尖對肩尖。肘尖裏扣。惟左腳落下。用彈力卽向前搶一步。名曰左搶步腿。如此循環。搶腿演進。但前進時。兩臂前後擺動。順勢臨空搶步而進。左右連續運動。欲停則左腳搶步時。停於右腳上。卽向成闊斧式。如第四圖。

4. Your left foot comes down in front and then your left leg lifts forward, the knee bending to make a ninety degree angle, the toes lifted so that the sole of the foot is facing slightly forward. At the same time, your right arm swings downward and to the rear, withdrawing to your waist, while your left palm carries upward as a willow-leaf palm, the fingertips at shoulder level, the elbow covering inward. When your left foot comes down, it does so with a snapping energy, going forward with a scraping step. This technique is called a “left scraping kick”. Continue in this way over and over, advancing with scraping kicks. While you advance as though walking on a tightrope, your arms swing forward and back. It is a continuous movement on both sides. If you want to stop, then when your left foot goes out with a scraping step, your right leg steps forward [into an empty stance] and you halt in the broad-ax posture [on the other side]. See photo 5.4:

生理上之關係

Physiological aspect:

左右交互。提腿搶步前進。所以使胯骨關節敏活舒暢。幷能振盪腸胃。旣助消化。亦可免便祕等症。並將各主要肌肉之功用。分析如左。

Both sides are worked equally as you lift each leg and advance with scraping steps, which livens the hips joints. This exercise can also stimulate the intestines and stomach, thereby aiding digestion, and can prevent constipation. Listed below are the main muscles that are being worked:

一、手前挑後擺。卽臂前舉與下垂之動作。

1. For the movements of the hand carrying forward and hanging down to swing behind:

甲、兩臂前舉。主要肌肉。

A. Raising the arm forward works these muscles:

三角 喙突肱 胸大 肱二頭等肌肉

deltoids, coracobrachialis, pectoralis major, biceps brachii.

乙、兩臂下垂。主要肌肉。

B. Lowering the arm behind works these muscles:

背闊 大圓 斜方下三分之一 胸大等肌肉 舉大腿 伸小腿

latissimus dorsi, teres major, lower trapezius, pectoralis major.

二、舉大腿與伸小腿之動作。

2. For the movements of raising the upper leg and extending the lower leg:

甲、舉大腿。主要肌肉。

A. Raising the upper leg works these muscles:

縫匠 闊筋膜張 恥骨 A股直等肌肉

sartorius, tensor fasciae latae, pectineus, rectus femoris.

乙、伸小腿。主要肌肉。

B. Extending the lower leg works these muscles:

股四頭 A股直 B股外 C股內 D股中等肌肉

Quadriceps (rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, vastus intermedius).

心理上之關係

Psychological aspect:

此節練習手腳輕捷靈敏。為自然跳躍之動作。當為少長咸宜之運動也。而於此種動作。又便易於學習。興趣亦濃。並能增人勇敢進取之心。關乎心理上。確有莫大之關係也。

This exercise trains nimbleness in the hands and feet, and promotes naturalness in jumping. Suitable for young and old alike, this is an exercise that is easy to learn and very enjoyable. It can also help increase a person’s fortitude, and so it is of great psychological relevance.

教育上之關係

Pedagogical aspect:

此節動作。可以發展敏速判斷決斷勇敢膽量啓發機警各優良之本性。而於教育上最有關係。要在教者之善用利導耳。

This exercise can develop quick wits, judgment, decisiveness, courage, boldness, awareness, and vigilance. These are excellent qualities to have, are especially relevant when it comes to teaching, and are indeed necessary for teachers to be able give good guidance.

–

第六節 舒緩運動(卽調和之動作)

Section 6: AN EXERCISE FOR SLOWNESS (i.e. a harmonizing movement)

種類

Type of exercise:

原地運用指腕及臂之擺動。幷轉動軀幹及腿之伸縮。

Standing in one place, your fingers, wrists, and forearms sway back and forth. The torso also twists and the legs are correspondingly extending and bending along with it.

術名

Name of the technique:

翻江搗海。

DIVERTING THE RIVER AND TURNING BACK THE SEA

實用要訣

Keys to the exercise:

要旨。係練吞吐連環之法。為擒拏鎖扣之用。欲研究武術之眞諦。以此為入門之要訣也。

The gist of the exercise is the practice of continuously inhaling and exhaling during these actions of seizing and locking. If you want to study the true essence of martial arts, this [coordinating of breath with movement] is a fundamental principle.

實習方法

Practice method:

預備

Preparation posture:

由立正抱肘。兩腳離開。與兩肩成垂直線。兩腿下彎為四十五度。成半馬式。

From standing at attention, elbows wrapped back, your feet spread apart to shoulder width and your legs bend forty-five degrees to make a half horse-riding stance.

一、兩拳變掌。向左側邏。右掌心向上。左掌心向下。同時軀幹順手勢向左轉。眼視兩掌。左臂平曲於胸前。右肘近貼於肋。小臂平屈於心前。兩手大拇指與四指成鉗形。兩手心上下相應。距離約七八寸許。如第一圖。

1. Your fists become palms and swing out to the left with your right palm facing upward and left palm facing downward, your torso going along with your hands by twisting to the left. Your gaze is toward your hands. Your left arm is horizontal and bent, the forearm in front of your chest, and your right elbow is near your [right] ribs, the arm bent, the forearm horizontal in front of your solar plexus. The thumb and fingers of each hand are making a slight claw shape. The palms are facing each other above and below, about three quarters of a foot apart. See photo 6.1:

二、兩掌卽翻轉。而臂則上下互換位置。右臂平曲於胸前。左肘近貼於肋。小臂平屈於心前。兩手手指仍成鉗形。兩手心仍上下相應。距離約七八寸許。